Help us make the FRA website better for you!

Take part in a one-to-one session and help us improve the FRA website. It will take about 30 minutes of your time.

- The effective implementation of the EU’s return policy is a pre-condition for an EU-wide rights-based immigration policy and is essential for the credibility of the common European asylum system. In accordance with Articles 13 and 18 of Directive 2011/95/EU, third-country nationals who risk persecution or serious harm in their own country must be granted international protection, even if they entered a Member State without permission. However, if everybody who comes to the EU remains physically in the EU without having the right to do so, this undermines the willingness of Member States – and of Europeans, more generally – to accord special treatment to people in need of international protection fleeing persecution or armed conflict who arrive in the EU spontaneously, without valid papers.

EU return policies and fundamental rights

- From a fundamental rights perspective, the implementation of EU return policies is a very sensitive area. Core fundamental rights guaranteed in the Charter are at stake. Without adequate safeguards, the return of third-country nationals may lead to violations, inter alia, of the prohibition of torture, inhuman or degrading treatment (Article 4 of the Charter), of the right of asylum (Article 18 of the Charter), of the principle of non-refoulement (Article 19(2) of the Charter) and of the prohibition of collective expulsions (Article 19(1) of the Charter). It may also result in unlawful interference with the right to liberty (Article 6 of the Charter), the rights of the child (Article 24 of the Charter) and, when seeking redress, the right to an effective judicial remedy (Article 47 of the Charter). It could also put human dignity at risk (Article 1 of the Charter).

- Any innovative approach or arrangement to increase the effectiveness of returns, including the possible creation of return hubs in third countries, needs to be assessed in light of these risks.

EU return rates

- There are no fully reliable statistics which show how many third-country nationals without the right to stay in the EU and subject to a return decision leave the territory of the Member States. There are also no reliable figures on the actual number of third-country nationals who are staying in the EU in an irregular situation.

- The statistical office of the EU, Eurostat, publishes yearly data on the number of people ordered to leave. Figure 1 below shows the figures for the past 10 years, where the number of third-country nationals ordered to leave the EU fluctuated between 400, 000 and 500, 000 people, except during the COVID-19 pandemic, when they were lower.

Alternative text: Line chart displaying the annual number of third-country nationals ordered to leave the EU from 2014 to 2023. The data range from 400,000 to 500,000 except for 2021, when the number dropped to some 340,000 individuals.

Source: Eurostat, Third-country nationals ordered to leave – annual data (rounded), data extracted on 11 November 2024. Data for 2024 are not yet available.

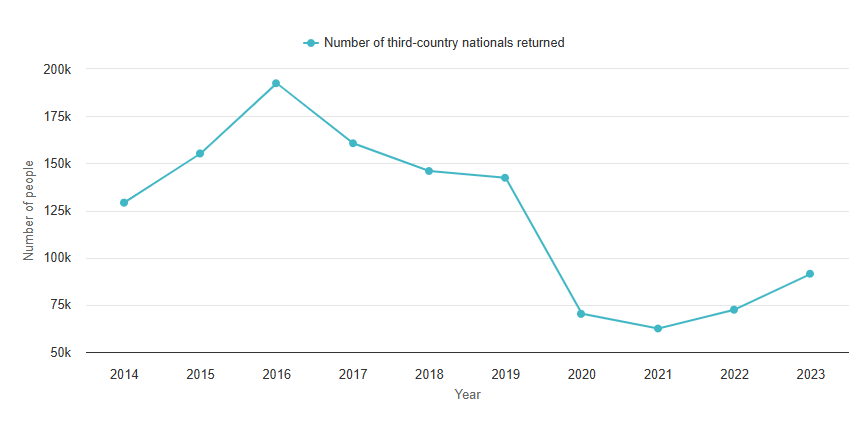

- The number of those third-country nationals who actually returned following an order to leave peaked at almost 200 000 in 2016. Following a significant drop during the COVID-19 pandemic, in 2023 it reached some 91 500.

Figure 2 – Number of third-country nationals returned from the 27 Member States, by year, 2014–2023

Alternative text: Line chart displaying the annual number of third-country nationals who returned from the EU from 2014 to 2023. The chart shows an increase from some 130,000 in 2014 to almost 200,000 in 2016. After that, the number dropped every year to reach a minimum of some 62,000 in 2021. After that, it increased to some 72,000 in 2022 and to some 91,000 in 2023.

Source: Eurostat, Third-country nationals returned following an order to leave – annual data (rounded), data extracted on 11 November 2024. Data for 2024 are not yet available. Data for 2014 and 2015 do not include figures for Austria, and data for 2021 do not include Lithuania. See Eurostat for further details on how to read the data.

- Even if the quality and reliability of these data are sometimes questioned (see International Centre for Migration Policy Development policy brief), and although the two Eurostat datasets are not directly comparable (for example, a person may receive a return decision in one year and be removed the next year, or there may be multiple return decisions for the same individual), they show a significant gap between the number of people ordered to leave and those who actually left the EU.

-

The reasons for low return rates are multiple [5] See, in this context, also Proposal for a directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on common standards and procedures in Member States for returning illegally staying third-country nationals – A contribution from the European Commission to the leaders’ meeting in Salzburg on 19 and 20 September 2018Proposal for a directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on common standards and procedures in Member States for returning illegally staying third-country nationals – A contribution from the European Commission to the leaders’ meeting in Salzburg on 19 and 20 September 2018, COM(2018) 634 final of 12 September 2018.

. These can be grouped into three different blocks.

- Reasons linked to administrative inefficiency of national return systems, which can be addressed through better coordination among national stakeholders and more procedural coherence, for example by systematically ensuring a rigorous assessment of international protection needs in the asylum procedure and improving communication between asylum and return authorities. The findings of the 2024 thematic Schengen evaluation on the effectiveness of return systems are expected to identify ways for Member States to make better use of existing tools and options, building on promising practices identified at the national level.

- Reasons linked to a lack of cooperation from the individual who is the subject of a return decision, for example to facilitate the identification process and obtain travel documents or to remain at the disposal of the authorities. Enhanced return counselling may be one way to counter such a lack of cooperation, together with other tools EU law already provides. These include pre-removal detention and alternatives to detention, when necessary and proportionate, to prevent absconding.

- Reasons linked to a lack of cooperation from the third country concerned, in refusing to identify and issue travel documents to the returnee or in taking other steps that delay returns and readmissions.

Initiatives in the EU to increase the effectiveness of returns

- In recent years, the EU and its Member States have been increasing efforts to make return policies more effective. In 2019, the EU legislator strengthened the operational role of Frontex in returns, paving the way for a more substantial Frontex engagement in supporting Member States in various ways, for example by offering return counselling and financing voluntary returns as well as post-return activities. In 2020, the Commission created the position of the EU Return Coordinator to bring together different strands of the EU’s return policy and support their consistent and coherent implementation. In 2024, the EU legislator adopted Regulation (EU) 2024/1349 on establishing a return border procedure for asylum applicants rejected in the asylum border procedure. In the same year, the Commission also launched a thematic Schengen evaluation of the effectiveness of the EU return system.

-

A proposed revision of the EU return directive, on which FRA had issued a legal opinion (FRA Opinion – 1/2019), remains pending, although a new legislative proposal on returns is expected to be tabled in early 2025 (see European Council conclusions of 19 December 2024, Conclusion No 19). In a letter to the Commission in May 2024, 15 Member States called for new solutions to address irregular migration to the EU and, as part of these, for exploring ‘potential cooperation with third countries on return hub mechanisms, where returnees could be transferred to while awaiting their final removal’. On 4 October 2024, 17 Member States called for new EU legislation for more effective returns in a non-paper. The European Council meeting of 17 October 2024 (European Council conclusions, Conclusion No 37) invited the Commission to take ‘determined action at all levels to facilitate, increase and speed up returns from the European Union, using all relevant EU policies’ and to submit a new legislative proposal on returns, as a matter of urgency [6] See also President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen’s letter to Commissioner-designate for Internal Affairs and Migration, 17 September 2024; and her letter of 16 December 2024 (and its annex) on migration matters, presented ahead of the European Council of 19 December 2024.

.