https://fra.europa.eu/surveys/index.php/833971?lang=en

In the past, civil society vessels rescued a significant number of migrants in distress at sea. These vessels seek to reduce fatalities and bring rescued migrants to safety in the European Union (EU). Since 2018, national authorities began administrative and criminal proceedings against crew members or vessels. They also tried to limit their access to European ports, causing delays in disembarkation and leaving rescued people at sea for over 24 hours waiting for a safe port.

- NGO ships involved in search and rescue in the Mediterranean and legal proceedings against them

- Difficulties in finding a safe port

NGO ships involved in search and rescue in the Mediterranean and legal proceedings against them

FRA published a note in October 2018 on Fundamental rights considerations: NGO ships involved in search and rescue in the Mediterranean and criminal investigations. The Agency regularly updates the two tables accompanying this note which describes criminal and administrative proceedings against non-governmental organisations (NGOs) or other private entities deploying search and rescue (SAR) vessels and aircraft.

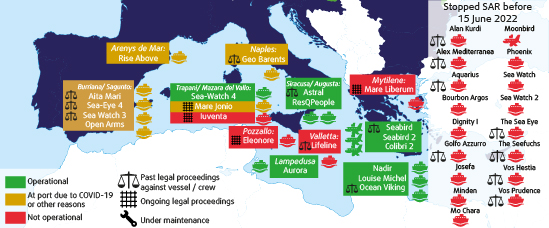

Since December 2021, two new administrative proceedings were initiated in the first half of 2022. In the same period, at least one SAR vessel stopped operating in the Aegean Sea due to the changes in Greek laws on the operation of rescue NGOs. The map below illustrates the position and situation of civil society SAR vessels and aircraft as of 15 June 2022. It includes those who had to stop their activities. It also indicates past and ongoing legal proceedings against the vessels and/or their crew members.

Map showing NGO assets involved in SAR operations in the Mediterranean Sea between 2016 and 15 June 2022

Due to ongoing criminal and administrative proceedings, vessel seizures, as well as mandatory maintenance work, some of these assets are blocked at ports and thus cannot carry out SAR operations. Out of 21 assets, eight currently operate (in green on the map). Out of these eight, only three perform SAR operations (‘Sea-Watch 4’, ‘Ocean Viking’ and ‘ResQPeople’). The remaining vessels and reconnaissance aircraft undertake monitoring activities. Five are blocked in ports pending legal proceedings (in red on the map). Seven vessels (in yellow) are currently docked due to other technical reasons. The map also displays vessels and/or their crew subject to past or current legal proceedings.

The two updated tables accompanying the note contain new developments over the past six months. Table 1 is an overview of all NGOs and their vessels and reconnaissance aircraft involved in SAR operations since 2016 in the Mediterranean. It also shows if they have been subject to legal proceedings. In the past six months, one reconnaissance aircraft started operating (‘Seabird 2’), one stopped operating (‘Moonbird’) and one NGO rescue vessel stopped monitoring (‘Mare Liberum’).

In addition to the few civil society rescue vessels deployed, state vessels and commercial ships also conduct rescue activities. Until 1 June 2022, to prevent any potential spread of Covid-19 rescued people were quarantined on board before landing or in ports right after their disembarkation (for more on quarantine vessels, see FRA’s Quarterly Bulletins on migration-related fundamental rights concerns).The Italian Health Ministry stopped this practice as of 1 June 2022.

Table 2 provides details on ongoing or closed investigations and administrative or criminal proceedings against private entities involved in SAR operations as of June 2022. It shows that since 2016 Germany, Greece, Italy, Malta, the Netherlands and Spain initiated 59 proceedings. Since December 2021, one new legal case opened in Italy, in addition to eight legal proceedings started in 2021. The new case concerned the administrative seizure of a vessel due to technical irregularities relating to maritime security which were identified after port authority inspections.

Overall, the most common issues detected by port authorities concerned the excessive number of passengers, ship assets not working properly, having too many life jackets on board, having inadequate sewage systems for the number of potentially rescued people, as well as for causing environmental pollution. No new case was opened against individual crew members on the basis of ‘aiding and abetting illegal immigration’ charges.

The applicable EU and international legal and policy framework remains unchanged. The original note’s related legal analysis can be found here. All information is up-to-date until 15 June 2022.

FRA will follow closely any further developments and continue to report regularly.

Download Table 2: Legal proceedings by EU Member States against private entities involved in SAR operations in the Mediterranean Sea (June 2022) (PDF, 297 KB) >>

Difficulties in finding a safe port

Since 2018, FRA publishes data on vessels that were not immediately allowed to disembark migrants and had to wait at sea to be assigned a safe port for more than 24 hours. This can be found in FRA’s annual Fundamental Rights Report (2020 – see table on p. 113, in 2021 – see Annex, and in 2022 – see also Annex). In 2022, as in previous years, rescue boats in the Central Mediterranean continued to remain at sea for a long time waiting for authorisation to enter a safe port. Delays in disembarkation risk the safety and physical integrity of rescued people. The overview table below describes instances FRA could corroborate when vessels with rescued people had to remain at sea for over a day waiting for a safe port. In 2022 (as of 15 June), at least 19 such instances were reported. There were 17 in 2021 and 22 in 2020.

The overview table in the tab Table – Vessels without a safe port shows that in the reported 19 instances, 3,716 rescued people (including at least 928 children) had to remain at sea for over a day until the national authorities allowed them to dock. In some cases, they waited while multiple rescue operations were carried out. In 12 cases, they waited for a week or more until the national authorities allowed them to dock.

Many asylum seekers, refugees and migrants rescued in the Central Mediterranean were picked up by the Libyan coastguards and brought back to Libya. Of those who left Libya by sea in 2022, 8,270 disembarked in Libya, compared to 32,425 in 2021, 11,891 in 2020, 9,225 in 2019 and nearly 15,000 in 2018. Italy renewed its cooperation agreement with Libya in July 2021. Malta signed a memorandum of understanding with Libya in May 2020 to cooperate in operations against irregular migration. As the political situation in Libya deteriorated, in July 2021, the International Organization for Migration and the UN Refugee Agency reiterated their call for states to refrain from returning anybody rescued at sea to Libya.

Legal framework

Assisting people in distress at sea is a duty of all states and shipmasters under international law. Core provisions on search and rescue (SAR) at sea are set out in the 1974 International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), the 1979 International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue (SAR Convention), and the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). In general, the shipmaster (of both private and government vessels) has an obligation to render assistance to those in distress at sea without regard to their nationality, status, or the circumstances in which they are found. A rescue operation terminates only when survivors are delivered to a ‘place a safety’, which should be determined taking into account the particular circumstances of the case, as specified by the 2004 amendments to the SAR Convention adopted by the International Maritime Organisation (IMO).

The IMO Guidelines on the treatment of persons rescued at sea further specify that a ‘place of safety’ is “a place where the survivors’ safety of life is no longer threatened and where their basic human needs (such as food, shelter and medical needs) can be met”. The selection of a place of safety should take due account of the principle of non-refoulement. Disembarkation where the lives of refugees and asylum seekers could be at risk of persecution, torture or other serious harm must thus be avoided.

The 2022 Joint Statement on Place of Safety by UN entities and the 2018 UN Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration (Objective 8) equally reaffirmed the above basic rules and principles.

In the context of controlling the EU’s external sea border under the Sea Borders Regulation (Regulation (EU) No. 656/2014), EU law incorporates the obligation to render assistance at sea and to rapidly identify a place of safety where rescued people can be disembarked in compliance with fundamental rights and the principle of non-refoulement. This prohibits disembarkation of rescued persons in a country where there is a risk of torture or ill-treatment applies irrespective of any request for asylum by the individual.

The duty to fully respecting the right to life (Article 2 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights and the European Convention on Human Rights) and to save lives at sea rests primarily on EU Member States. These core obligations cannot be circumvented under any circumstances, including for considerations of external border control.

As part of the new Pact on Migration and Asylum, the European Commission Recommendation (EU) 2020/1365 on cooperation among Member States concerning SAR operations carried out by private vessels encouraged Member States to ensure rapid disembarkation in a place of safety, where the fundamental rights of rescued people are guaranteed, in conformity with the EU Charter and the principle of non-refoulement.