Help us make the FRA website better for you!

Take part in a one-to-one session and help us improve the FRA website. It will take about 30 minutes of your time.

Civic space is the environment that enables civil society to play a role in political, economic and social life of our societies. In particular, civic space allows individuals and groups to contribute to policy-making that affects their lives.

OHCHR (n.d.), ‘OHCHR and protecting and expanding civic space’.

A vibrant and engaged civil society can support the implementation of EU policies in many areas that are key for upholding and protecting fundamental rights. Such policies include the EU Strategy to strengthen the application of the Charter of Fundamental Rights in the EU; the European Democracy Action Plan; and relevant action plans on anti-racism, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer and other minority gender identities and sexualities (LGBTIQ+) equality, Roma inclusion, the rights of the child, disability, victims’ rights, gender equality and migrant integration.

European institutions and international and regional human rights organisations emphasise the important role of civil society in safeguarding and promoting human rights and democracy. Yet civil society organisations (CSOs) face diverse challenges across the EU that hamper their ability to promote human rights.

The European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) has pointed to a number of significant hurdles for CSOs since it issued its report Challenges facing civil society working on human rights in the EU in 2018, and in its subsequent annual updates. CSO face threats and attacks, excessive legal and administrative restrictions, insufficient resources and access to information, and are often not properly involved in policy and decision-making.

This report highlights key developments regarding the civic space in the EU in 2022. The analysis draws on the responses of almost 400 civil society organisations, umbrellas and networks to the Agency’s annual consultation 2022 on civic space; research carried out by FRANET in 2022 resulting in country reports on relevant legal and policy developments in all 27 EU Member States and in three accession countries; and focus groups, meetings, interviews and desk research.

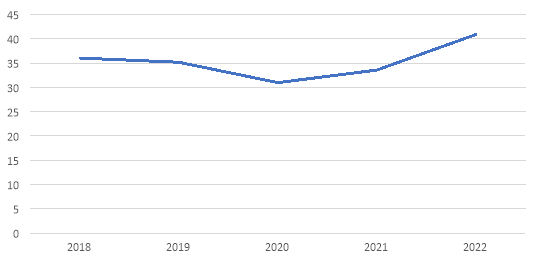

Based on evidence collected by FRA, the nature and depth of challenges vary across Member States. However, across all Member States, CSOs have expressed concerns in FRA’s annual consultations and have indicated that a number of problems identified has persisted in recent years. In 2021 and 2022 in particular, their responses were overall more negative than in other years because of the impact of measures to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, FRA has identified a range of positive developments that have fostered an enabling environment for the promotion of human rights and democracy. In the past five years, the understanding of the challenges that CSOs face in the EU has been ever-increasing. In 2022–2023, all three major EU institutions acknowledged for the first time civic space pressures in the EU in official documents (the European Parliament resolution on civic space in the EU, the European Commission report on the application of the Charter and civic space and the Council conclusions on the role of the civic space in protecting and promoting fundamental rights in the EU). Donors – including the European Commission and the European Economic Area and Norway Grants – increasingly provide funding with a focus on addressing civic space challenges.

Several Member States have set up or improved their structures and processes for ensuring meaningful civil society engagement. CSOs themselves increasingly speak out about attacks against them and cooperate more closely in face of pressures on them and their work.

According to the United Nations (UN) guidance note on the protection and promotion of civic space, “civic space is the environment that enables people and groups – or ‘civic space actors’ – to participate meaningfully in the political, economic, social and cultural life of their societies”. Although civic space thus goes well beyond CSOs, this report is based on evidence that FRA collected from CSOs.

A legal environment conducive to ensuring an open civic space requires a strong legislative framework that protects and promotes the rights to freedom of association, peaceful assembly and expression, in conformity with international human rights law and standards - notably the EU Charter of fundamental rights, the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). The UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders, although not legally binding, contains principles and rights that are based on human rights standards enshrined in other legally binding international instruments.

Developments in the legal environment affecting CSOs vary across EU Member States. A decrease in challenges related to emergency laws is visible from 2020 and 2021 to 2022, corresponding to the gradual lifting of the emergency provisions adopted in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Other legal challenges remained similar to those encountered in previous years, with CSOs reporting issues related to accessing information, legislation regarding civil dialogue, threats regarding the dissolution of NGOs on grounds of public order, attempts to tighten rules on assemblies , disproportionate policing, and negative side effects of legislation in the areas of data protection, transparency and lobbying, tax and charitable status, counter-terrorism and anti-money laundering.

Positive developments include continued efforts in a few countries to improve the legal frameworks for exercising the right to peaceful assembly, to modernise existing rules and ease bureaucratic requirements for CSOs, and to reform registration systems and rules regarding public benefit status.

A particular challenge concerns strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPPs). These are unfounded or abusive court procedures against natural or legal persons engaging in public matters whom the claimant wants to silence. In April 2022, the European Commission proposed a directive and a recommendation against SLAPPs. CSOs sometimes face SLAPPs when they take positions on issues in their advocacy work, for example when someone claims to have been defamed by their public statements. This may have a chilling effect on their willingness to work on certain issues.

As part of their action to strengthen the application of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (the Charter) and the rule of law, EU institutions should regularly monitor the civic space in the EU, closely involving civil society actors and other human rights defenders. The methodology of the European Commission’s ‘CSO Meter’, applied in Eastern Partnership countries, could be adapted for this purpose. The monitoring results could be included in the European Commission’s annual reports on the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights and as part of rule of law reporting, together with recommendations and strategic guidance for improving the situation.

EU institutions and Member States – when acting within the scope of EU law – should ensure that EU and national laws strengthen the rights to freedom of expression, peaceful assembly, and association. Furthermore, they should ensure that the transposition and application of EU rules do not result in disproportionate restrictions on civil society activities. Furthermore, the European Commission should continue bringing infringement proceedings where necessary to protect the civic space, and should ensure that rulings by the Court of Justice of the European Union are fully implemented.

Furthermore, the European Commission should consistently ensure that civil society and other relevant stakeholder are engaged in appropriate ex ante assessments and in any consultations during the preparation or review of EU legislation. This ensures that provisions that potentially affect civic space and civic freedoms can be detected early on. It also helps to determine, in the process of incorporating and implementing EU law at national level, provisions that could lead to unintended limitations at this level.

The EU and Member States should also ensure that legislation does not unnecessarily t restrict civic space,, and that it complies with international human rights standards and principles, including Article 10 ECHR & 19 ICCPR (freedom of expression) and Article 11 ECHR and 21 & 22 ICCPR (freedom of assembly and association) . Human rights CSOs and their members need to be able to exercise their rights fully and without unnecessary or arbitrary restrictions on carrying out their work. CSOs therefore need states to fully implement their obligation under international human rights standards, including in particular the freedom of expression, peaceful assembly and association s . An enabling environment allows CSOs to fully enjoy their rights, including the right to access public funding and resources, and the right to take part in public affairs.

As discussions on the Commission’s anti-SLAPPs proposal are ongoing, Member States should take effective measures against SLAPPs, to fulfil their obligations to uphold the rights to freedom of expression and association, among other reasons. Such measures should include reviewing existing legislation to limit the use of SLAPPs. Furthermore, practitioners in the legal field, including both judges and lawyers, should be adequately trained on aspects of freedom of expression to enable them to recognise and appropriately address SLAPPs.

Threats and attacks against CSOs and human rights defenders by both public and private players persisted across the EU in 2022, targeting organisations, staff and volunteers.

Threats and attacks take multiple forms. Public authorities use SLAPPS, unnecessary administrative hurdles, smear campaigns, the criminalisation of certain activities and excessive surveillance, CSOs report. Defenders also report receiving verbal threats offline and online, intimidation and harassment, and physical attacks by private players. FRA’s 2022 findings show that overall problems persist, with no improvements across the EU from previous years.

In several Member States, CSOs and human rights defenders working in specific policy areas report they are increasingly subject to hostile environments, with intimidation, legal proceedings and smear campaigns against their work. This particularly affects migrant rights defenders, LGBTIQ+ rights defenders, women’s rights defenders, sexual and reproductive health and rights defenders, environmental rights defenders, anti-racism activists and child rights defenders, as FRA’s research for this report indicates.

Member States should encourage that crimes committed against CSOs and human rights defenders are reported, and ensure they are properly recorded, investigated and prosecuted.

Building on the existing external EU human rights defenders mechanism, the EU could consider setting up a similar mechanism for inside the EU. Such a mechanism should allow CSOs and human rights defenders to report attacks, register alerts, map trends, build capacity, and provide timely and targeted support to victims. In this context, there is also a need for Member States to establish, bolster and strengthen national level protection mechanisms which would help detect, and act in response to, attacks and reprisals against human rights defenders. According to the Paris Principles, National Human Rights Institutions have a role in protecting and supporting other human rights defenders and CSOs.

Member States should refrain from criminalising or taking legal or non-legal actions that unduly hamper the operation of CSOs, including those providing legal, humanitarian and other assistance to asylum seekers and other migrants, or undertaking search and rescue (SAR) at sea. The European Commission should continue to pay the utmost attention to threats against CSOs and human rights defenders, including in its bilateral discussions during the preparation of its annual rule of law report and the related country-specific recommendations.

CSOs’ work is essential for strengthening democracy, addressing complex issues, promoting innovation, encouraging local solutions, building capacity, fostering collaboration and partnerships; and overall ensuring long-term improvements in human rights. This important work needs to be adequately resourced. However, access to resources remains an ongoing concern for CSOs, as regards both the availability of funding relevant to their work and the accessibility of such funding due to bureaucratic requirements. Rules on limitations to foreign funding constitute an additional obstacleto the functioning of CSOs. As the OSCE/ODIHR-Venice Commission Joint Guidelines on Freedom of Association note, “[a]ssociations shall have the freedom to seek, receive and use financial, material and human resources, whether domestic, foreign or international, for the pursuit of their activities.”[1] OSCE/ODIHR-Venice Commission Joint Guidelines on Freedom of Association, Principle 7, para. 32.

Overall, donors have gradually started to adjust their funding to take into account the needs of CSOs, giving more consideration to advocacy on civic space, and capacity building particularly for security-related issues.

One significant change from previous years is that the European Commission has considerably stepped up its efforts to fund CSOs working on human rights issues, in particular through the Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values (CERV) Programme. This programme is the largest to date supporting civil society in the EU, and pilots more flexible funding approaches. At the same time, the 2021 Common Provisions Regulation (governing eight large EU funds) introduced compliance with the Charter as an ‘enabling condition’, encouraging Member States to involve civil society and other fundamental rights actors in the monitoring of the Charter’s implementation. Moreover, the Common Provisions Regulation and the Commission’s European Code of Conduct on Partnership call for strong partnerships, including with CSOs.

EU institutions and Member States should ensure that CSOs have access to diverse pools of resources and that EU and Member State rules for EU-based CSOs’ access to funding from domestic or foreign sources respect the principle of proportionality and comply with EU primary law. Financial support offered should cover the full range of civil society activities, beyond service provision, covering advocacy and watchdog functions, capacity building, litigation, cooperation and network building, peer exchange across borders, community engagement, resilience and security.

Beyond project funding, core funding and multiannual funding cycles could strengthen civil society and ensure the sustainability of its human rights work. It is crucial that funding becomes readily available and accessible, in particular for grassroots organisations. In this context, the European Commission could consider using a re-granting mechanism as it does in the CERV values fund also for other funding lines available to CSOs.

The European Commission should continue to ensure that rules regulating CSOs’ access to and use of foreign funding comply with Article 63 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) and Articles 7, 8 and 12 of the Charter. It should also make sure that they respect the principle of proportionality and overall comply with EU primary law as interpreted by the Court of Justice of the European Union. Moreover, the EU and its Member States could reinforce efforts to promote the exchange of information and good practices in this area, involving CSOs to enable them to share their experiences.

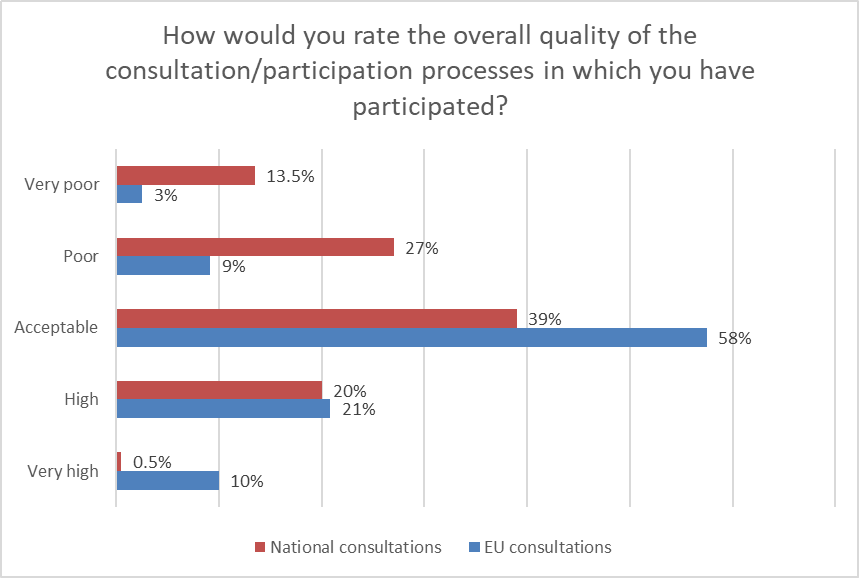

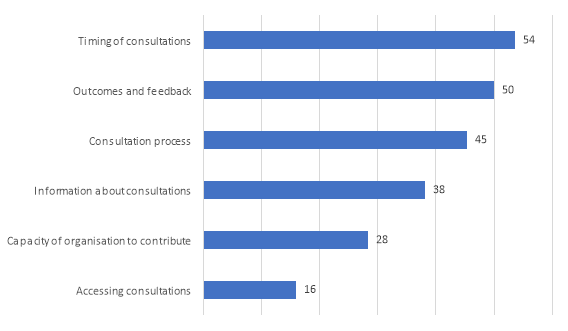

Many Member States initiated or consolidated participation mechanisms in 2022, both at national and local levels. Notwithstanding, procedures for CSOs to participate effectively in policymaking and decision making remain patchy, and CSOs are often unable to access relevant information or clear standards or guidelines to support their contribution. Challenges that CSOs face include the limited interest of policymakers in consulting meaningfully, difficulties in accessing consultations, weaknesses in the consultation process itself, insufficient feedback on follow-up after consultations and the insufficient capacity of organisations to contribute to consultations, including due to a lack of funding for such processes. These challenges are exacerbated for organisations working with those at risk of exclusion.

However, in general the principle of cooperation between CSOs and public authorities in ensuring the implementation of laws and policies related to fundamental rights has been strengthened in recent years. The EU Strategy to strengthen the application of the Charter of Fundamental Rights in the EU, and many sectorial EU action plans and strategies, call for the engagement of CSOs in the design, implementation and evaluation of relevant measures. Partly reflecting the positive cooperation experiences made during the COVID-19 pandemic and the response to the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine, Member States have developed additional initiatives promoting the more meaningful cooperation with and participation of CSOs. Nevertheless, cooperation is often ad hoc and incident-specific, as FRA’s evidence shows, for instance in the field of hate crime reporting.

To implement Article 11 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU), the EU could consider establishing a dedicated EU policy framework with common guidelines allowing for open, transparent and regular dialogue between the EU institutions and civil society at EU, national and local levels. It should include funding for appropriate processes, training of officials, and regularly organising consultations and exchanges, including through the representations of the European Commission and the European Parliament in the Member States. It should emphasise access to information and the participation of CSOs representing excluded or underrepresented groups.

There is a need to develop sustainable and structured, institutionalised forms of cooperation, and to establish a culture of trust and transparency; respect CSOs’ independence; ensure CSOs’ broad representation and inclusive participation; and formalise commitments, including through institutional arrangements, ensuring the sustainability of cooperation.

There is also a need to ensure adequate financial and technical support for CSOs and human rights defenders to take up participation, consultation and dialogue opportunities. Specific measures are necessary to reach out to marginalised and excluded groups.

Civil society’s expertise, services, advocacy and watchdog role are key to the implementation of fundamental rights in the EU. Therefore, FRA reports on civic space developments across the EU have been published annually since 2018.[1]

Various challenges and pressures hamper the important work of CSOs and human rights defenders across the EU in the areas of human rights, democracy and the rule of law. These are referred to as ‘civic space challenges’.

The graphs in this report summarise the responses from representatives of close to 400 CSOs working in the area of human rights at EU, national and local levels in the EU. Their responses cover their experiences in civic space in 2022.

Reports by international organisations and a range of CSOs, and by FRA,[2] have pointed to persisting serious challenges for civil society in the EU, limiting its role and contribution to the functioning of democracy and the rule of law (see Figure 1). In 2022, the effects of the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine further exacerbated some of these challenges (see Figure 2).

FRA’s research and the findings from its annual consultations with civil society point to patterns of challenges for CSOs regarding:

— the legal frameworks governing their work and their participation in democracy and the rule of law;

— access to resources;

— participation in policymaking and decision making;

— operating in a safe environment.

The nature and extent of these challenges vary considerably across the EU. FRA’s findings show that across EU Member States, the environment for the operation of CSOs remains challenging. The Franet country studies on civic space provide a more detailed description of the situation in each Member State.[3]

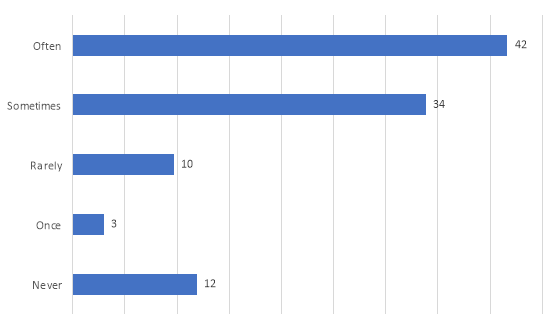

Figure 1 – How often CSOs faced barriers in conducting their human rights activities in 2022 (%)

Type your alternative text here.

Notes: Question: “In the last 12 months, did you face any barriers in conducting your activities for human rights and the rule of law?” N = 359.

Source: FRA’s civic space consultation 2022

Figure 2 – General conditions for CSOs working on human rights – respondents indicating ‘bad’ or ‘very bad’ (%)

Type your alternative text here.

Notes: Question: “How would you describe in general the conditions for CSOs working on human rights issues in your country today? (very good/good/neither good nor bad/bad/very bad)” The figure shows the percentage of those responding ‘bad’ or ‘very bad’. 2018, N = 136; 2019, N = 145; 2020, N = 297; 2021, N = 286; 2022, N = 318.

Source: FRA’s civic space consultations, 2018–2022

Figure 3 – Organisations perceiving a change in their own situation in 2022 – respondents indicating ‘deteriorated’ or ‘greatly deteriorated’(%)

Type your alternative text here.

Notes: Question: “Thinking about your own organisation, how has its situation changed in the past 12 months? (greatly improved/improved/remained the same/deteriorated/greatly deteriorated)” 2018, N = 133; 2019, N = 202; 2020, N = 393; 2021, N = 387; 2022, N = 407. For 2018, the question referred to the past three years.

Source: FRA’s civic space consultations, 2018-2022

A higher number of organisations perceived their situation as having improved from the previous year in 2022 than in previous consultations, and a lower number witnessed a deterioration (18 % compared with 28 % in 2021) (Figure 3).[4] To a large extent this can be related to the ending of COVID measures, notably emergency measures which greatly affected CSOs.[2] FRA (2021), COVID-impact on civil society work. Results of consultation with FRA’s Fundamental Rights Platform.

In terms of policy measures by authorities, FRA’s research reveals both positive and negative developments in 2022 across the EU. Positive steps in several Member States include policy measures creating an environment more conducive to the development of civil society , the strengthening of cooperation between public authorities and CSOs including through setting up cooperation bodies, and the improvement of frameworks for participation. For example, some Member States have created infrastructures aimed at providing space for dialogue, channelled targeted support to civil society, or undertaken specific commitments to create an enabling environment in national action plans for an open government. CSOs have also been active in their efforts to improve the policy framework in which they operate, including through coalition building.[5]

The key role of civil society is reflected in the EU treaties. Article 11 (2) of the TEU and Article 15 (1) of the TFEU consider civil dialogue and civil society participation as tools for good governance. It is also reflected in relevant EU policy documents, such as the EU Strategy to strengthen the application of the Charter of Fundamental Rights in the EU, the European Democracy Action Plan, and action plans on anti-racism, LGBTIQ+ equality, Roma inclusion, children’s rights, disability, victims’ rights, women’s rights and migrant integration.

In 2022–2023, all three major EU institutions have for the first time acknowledged civic space pressures in the EU in official documents:

● the European Parliament resolution on civic space in the EU (March 2022)

● the European Commission report on the application of the Charter and civic space (December 2022)

● the Council Conclusions on the role of the civic space in protecting and promoting fundamental rights in the EU (March 2023).

2022 was an important year for civic space-related developments. The European Commission dedicated its annual report on the application of the Charter to the topic ‘A thriving civic space for upholding fundamental rights in the EU’. It reviewed the situation of civil society organisations and other human rights defenders, concluding that they need more support and that their operating environment needs improvements.[6]

The Commission announced in the report that it would launch targeted dialogue with stakeholders through a series of thematic seminars on safeguarding civic space. The seminars focused on how the EU can further develop its role to protect, support and empower CSOs and rights defenders to address the challenges and opportunities identified in the report. The outcome of the seminars will be discussed at a high-level conference in November 2023.[3] European Commission (2023), Summary Report, A thriving civic space for upholding fundamental rights in the EU: looking forward - Follow up seminars to the 2022 Report on the Application of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights (forthcoming)

Proposals for EU legislation of direct relevance to CSOs were also put forward in 2022.

In February 2022, the European Parliament called for “a dedicated, comprehensive strategy to strengthen civil society in the Union, including by introducing measures to facilitate the operations of non-profit organisations at all levels”.[7]

In particular, the Parliament called for a legislative initiative to create a statute for European cross-border associations and non-profit organisations.[8] The resolution calls on the Commission to recognise and promote the public benefit activities of non-profit organisations by harmonising the conditions for granting public benefit status within the EU. In response to the European Parliament’s call, the Commission adopted, on 5 September 2023, a proposal for a directive on European cross-border associations[4] COM(2023) 516.

. The proposal supplements the existing national legal forms of associations with a new legal form of non-profit associations specifically designed for cross-border purposes (ECBA). It seeks to ensure that ECBAs can fully enjoy the benefits of the internal market, simplify associations’ cross-border activities in the EU and, as a consequence, promote the fundamental rights of the associations and their members., simplifying associations’ cross-border activities in the EU, and, as a consequence, promoting the fundamental rights of the associations and their members. After registration in one Member State, the proposal allows automatic recognition of ECBAs across the union. It also provides for harmonised rules on the transfer of registered office[5] Cross-border associations in the EU (europa.eu).

.

In addition, in April 2022 the European Commission proposed a directive on SLAPPs. These will most probably be adopted at the end of 2023 (for details, see Section 2.2).

Surveillance was also a prominent topic in 2022. Following alleged abuses in the use of Pegasus and similar surveillance software against a variety of targets, including CSOs, the European Parliament set up a committee of inquiry to investigate them.[9] The committee published a report on its findings in May 2023.[10]

Moreover, in September 2022, the European Commission proposed a European media freedom act, consisting of a proposed regulation and a recommendation for editorial independence and ownership transparency in the media sector.[11] The proposed legislation included safeguards against political interference in editorial decisions and against surveillance. It focuses on the independence and stable funding of public service media, and on the transparency of media ownership and of the allocation of state advertising. The draft envisages the formation of a European board of media services. The board will, among other things, organise a “structured dialogue between providers of very large online platforms, representatives of media service providers and representatives of civil society” to foster access to diverse independent media on very large online platforms and discuss experiences and best practices.[12]

In this regard, it is of interest to mention that the Digital Services Act, which entered into force in 2022,[13] establishes various mechanisms allowing for CSO engagement, including the possibility to launch complaints, to engage in the identification of societal risks and their evolution, in the context of drawing up codes of conduct and crisis protocols.[14]

Finally, 2022 also saw the preparations of the European Commission’s Defence of Democracy Package. The plan was announced in the President of the Commission’s State of the Union speech. Whereas the inititive is aimed at promoting transparency and fighting foreign interference, concerns were raised by some stakeholders about possible negative implications for fundamental rights and ultimately the work of CSOs.[15] The Commission announced in June 2023 that it would further consult and gather additional information as part of a full impact assessment. According to the European Commission, enhanced transparency and democratic accountability, freedom of expression and association are carefully being looked at in this context..

In its December 2022 report on civic space in the EU, the European Commission underlined that CSOs and rights defenders continue to report a range of challenges and restrictions that limit their ability to carry out their activities.[16] The European Commission found during its consultation for the report that 61 % of responding CSOs had faced obstacles that limit their ‘safe space’.[17] As a follow-up to its report, the Commission convened three expert seminars. One of them focused on protection.[18]

Leading civil society umbrella organisations organised a major gathering in December 2022. It brought together over 100 representatives of civil society, EU and international institutions, and donors to discuss how to enable, protect and expand Europe’s civic space. Those gathered developed recommendations for the European Commission.[19] At the gathering, the organisations called for, among other things, “an EU mechanism to protect civil society and human rights defenders that should be built on the example of the existing external EU human rights defenders’ mechanism protectdefenders.eu, the mechanism developed by DG IntPA [the Directorate-General for International Partnerships] to support civil society in the External Action, as well as the Council of Europe Platform for safety of journalist[s] and the UN Special Procedures”.[20]

The Citizens, Equality, Rights and Values (CERV) programme, introduced in 2021, continued to provide funding for civil society actors in the EU in 2022.[21] The programme also gives umbrella CSOs the opportunity to receive core funding and to regrant it to their member organisations. While CSOs praise these developments overall, they continue to criticise the resulting administrative burden and lack of flexibility.[22]

Article 11 of the TEU defines civil dialogue as an essential component of participatory democracy and requires EU institutions to “give citizens and representative associations the opportunity to make known and publicly exchange their views in all areas of Union action” and to “maintain an open, transparent and regular dialogue with representative associations and civil society”. The European Commission considers the participation of civil society as key to ensuring good-quality legislation and the development of sustainable policies that reflect people’s needs.[23]

Several EU strategies and action plans in the field of fundamental rights envisage the setting up of various forms of civil society forums/platforms, working groups, etc., to facilitate dialogue and structured cooperation between authorities and civil society and the implementation of the strategies and plans. Such strategies and action plans often call for the adoption of national action plans, which can also benefit from civil society participation.

For instance, under the EU Roma Strategic Framework for Equality, Inclusion and Participation for 2020–2030, the European Commission set out to facilitate the participation of Roma non-governmental organisations (NGOs) as full members of national monitoring committees for all programmes addressing needs of Roma communities. It has thereby capacitated and engaged at least 90 NGOs in EU-coordinated Roma civil society monitoring, encouraging the participation of Roma in political life at local, regional and EU levels.[24]

Similarly, the Action Plan on Integration and Inclusion 2021–2027 concerning migrant integration refers to the European Commission’s launch of an expert group on the view of migrants. The group is composed of migrants and organisations representing their interests, to be consulted on the design and implementation of future EU policies in the field of migration, asylum and integration.

Box X X – Promising practice: the Humanitarian Partnership Watch Group

The Humanitarian Partnership (former Framework Partnership Agreement) Watch Group defines the contractual relationship – i.e. the regulations and responsibilities - between the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Humanitarian Aid (DG ECHO) and humanitarian organisations. An EU Humanitarian Partnership Certificate is awarded to organisations that are considered suitable to apply for EU funding for the implementation of humanitarian aid actions, based on a positive assessment of their partnership application. The Humanitarian Partnership Watch Group represents the views of all DG ECHO’s NGO partners in the monitoring, review, and consultation of all matters relating to the Humanitarian Partnership, and it works towards a common interpretation and consistent application of their partnership in a way that addresses CSOs not only as beneficiaries, but also as partners.

Source: European Commission DG ECHO, Working with DG ECHO as an NGO partner

Building on the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and related treaties, the UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders of 1998 explicitly lists the rights and responsibilities of human rights defenders.[25]

In line with the overall UN General Assembly mandate to promote and protect human rights,[26] the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights seeks to expand civic space and to strengthen the protection of human rights defenders around the globe. His office monitors and advocates around numerous cases of defenders under threat. It also acts as the custodian of Sustainable Development Goal indicator 16.10.1 on verified cases of killing, kidnapping, enforced disappearance, arbitrary detention and torture of journalists and associated media personnel, trade unionists and human rights advocates. In their practice, the UN human rights treaty bodies have raised various issues concerning civic space and the need for an enabling environment for the activities of CSOs and human rights defenders.[6]See among others Human Rights Committee, General Comment No. 36 on Right to Life – adopted 30 October 2018, paras. 23 and 53; General Comment No. 37 on Right of peaceful assembly – adopted on 23 July 2020, para. 30; General recommendation No. 39 on the rights of Indigenous Women and Girls – released on 31 October 2022, especially paras. 45-46.

The mandate of the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights defenders to promote the Declaration on Human Rights Defenders’ effective implementation was established in 2000.[27] In 2022, the Special Rapporteur published, among other things, a report on defenders of the rights of refugees, migrants and asylum seekers,[28] and made numerous statements in recognition of issues specific to human rights defenders.[29] The work of most, if not all, of the UN Human Rights Council-appointed special procedures mandate holders[30] touches on issues related to human rights defenders and civic space.

Moreover, following the establishment of the mandate of the Special Rapporteur on Environmental Defenders under the Aarhus Convention in October 2021, the Meeting of the Parties to the Aarhus Convention elected Michel Forst as the first special rapporteur in this area in June 2022.[31]The special rapporteur’s primary role is to provide a rapid response to protect environmental defenders from persecution, penalisation and harassment.

|

Box 1 – Legal corner – New Special Rapporteur on Environmental Defenders under the Aarhus Convention Article 3 (8) of the Aarhus Convention provides that “Each Party shall ensure that persons exercising their rights in conformity with the provisions of this Convention shall not be penalized, persecuted or harassed in any way for their involvement.” The mandate of the Special Rapporteur on Environmental Defenders is to take measures to protect any person who is either: (a) Experiencing persecution, penalization or harassment, or (b) At imminent threat of persecution, penalization or harassment in any way, for seeking to exercise their rights under the Aarhus Convention. The mandate of the Special Rapporteur covers penalization, persecution or harassment by any state body or institution and by private natural or legal persons. The Special Rapporteur also takes a proactive role in raising awareness of environmental defenders’ rights under the Aarhus Convention. Source: United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) (n.d.), ‘Mandate and functions of the Special Rapporteur’ |

Similarly, the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights continued to support human rights defenders and civil society in the Council of Europe area, and to promote an enabling environment for them by various means in accordance with her mandate. This included meeting them regularly; reporting about their situation; intervening in cases where they had faced risks to their personal safety, liberty and integrity; participating in the proceedings before the European Court of Human Rights and the process of implementation of its judgments, and co-operating with other international mandates and stakeholders throughout 2022.[7]([1]) Human rights defenders - Commissioner for Human Rights - Commissioner for Human Rights (coe.int)

The Council of Europe’s Parliamentary Assembly also continued to work on civic space issues. It adopted a report and a recommendation on the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on civic space.[32] The assembly also continued its work on a report containing a resolution on the issue of transnational repression, which was subsequently adopted in 2023.[33]

In 2022, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) published a resilience tool for national human rights institutions[34] and offered a range of training programmes for civil society on human rights monitoring and related security issues.

In December 2022, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) published a landmark report entitled The protection and promotion of civic space: Strengthening alignment with international standards and guidance, which covers the EU.[35] The OECD will also publish a practical guide for policymakers on the protection and promotion of civic space in 2024. In addition, the OECD is conducting country assessments on civic space, which are qualitative reviews of the laws, policies, institutions and practices that support civic space in OECD member and partner countries.[36] In 2022–2023, two EU countries were covered: Portugal[37] and Romania.[38]

|

Box 2 – Promising practice – Intergovernmental organisations’ Contact Group on human rights defenders The informal Contact Group on human rights defenders was set up in spring 2019 at the initiative of FRA and ODIHR to establish the ongoing, practical exchange of information among staff in intergovernmental organisations and EU institutions. Staff responsible for cooperation with civil society and for supporting human rights defenders from almost 20 such bodies meet at least three times a year online to discuss their ongoing and upcoming activities. This improves the coordination of their activities and their cooperation with other organisations and fosters synergies with a view to better supporting human rights defenders in Europe. Source: FRA |

FRA has granted three EU candidate countries – Albania, North Macedonia and Serbia – observer status. Hence, it covers these three countries in its work. Franet research on civic space also covers these, and FRA’s 2022 civic space consultation collected responses from 30 CSOs across these countries. Developments in civic space in Albania, North Macedonia and Serbia show similar patterns to those in the EU.

The main difficulties that CSOs encountered in 2022 in these three countries concerned access to information, legislation on civil dialogue and consultations, transparency and lobbying laws, and anti-money laundering measures.[39] Fewer CSOs said their organisation’s conditions had worsened compared with the previous year in 2022. Still, around 20 % of respondents saw their situation as having deteriorated, whereas roughly 6 % believed it had greatly deteriorated.[40] In comparison, 16 % in EU Member States said their situation had deteriorated, and around 2 % said it had greatly deteriorated.[41]

One quarter of responding CSOs experienced difficulties in terms of enjoying their right to freedom of peaceful assembly.[42] In Albania and Serbia, CSOs referred to obstacles to exercising this right. In these countries, human rights organisations carried out activities aimed at monitoring the compliance of police procedures with national and international standards on peaceful assembly. In Serbia, in September 2022, public authorities attempted to ban the peaceful LGBTIQ+ EuroPride march and restrict protests for environmental rights.[43]

North Macedonian and Serbian CSOs complained of a lack of an enabling environment. Problems arose particularly in their cooperation with public authorities. CSOs reported that SLAPPs are used to silence civil society.

In Serbia, environmental defenders and activists denouncing bad health practices during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic faced lawsuits. In North Macedonia, a working group composed of state institutions’ representatives and CSOs drafted a legislative proposal aimed at providing a process for legal gender recognition. It was withdrawn after reaching the parliament, following fake news and transphobic propaganda.[44] These events are reflected in the overall trend evident from FRA’s civic space consultation, where almost half of respondents reported that their organisation was a victim of negative media reports and/or campaigns in 2022. Moreover, almost half of respondents experienced online and/or offline threats or harassment due to their work.[45]

A recurring negative pattern in all three countries, particularly Albania and Serbia, concerns environmental defenders, who reportedly often face lawsuits and harassment. However, promising practices indicate that CSOs are willing to proactively and collectively protect civic space and to promote citizens’ participation in decision-making processes. This was, in some cases, achieved through civil society-led umbrella initiatives. For instance, in North Macedonia the Skopje-based European Policy Institute and the Deliberative Democracy Lab at Stanford University organised a third deliberative poll on the topic of elections and electoral reforms, which involved about 150 citizens.[46]

In other cases, cooperation between CSOs and public authorities led to significant results. In Albania, the non-profit sector, the state and financial authorities jointly developed a methodology aimed at assessing the risk of terrorist financing in the non-profit sector. Finally, a training initiative in North Macedonia aimed to raise awareness of corruption, build capacity to tackle it and enhance transparency. It brought together the CSO Center for Civil Communication and employees in local government and local public enterprises.[47]

Another relevant development concerns the Albanian NHRI, which was granted additional competences to serve as a focal point for monitoring of challenges facing human rights defenders in 2022.[8]ENNHRI's rule of law report - Albania national report from 2022 https://ennhri.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Albania_CountryReport_RuleofLaw2022.pdf

A legal environment conducive to an open civic space requires a strong legislative framework that protects and promotes individuals’ and organisations’ rights to freedom of association, peaceful assembly and expression in conformity with international human rights law and standards.[48] The UN Declaration on Human Rights Defenders, although not legally binding, contains principles and rights that are based on human rights standards enshrined in other legally binding international instruments.

Most of these rights apply not only to the people working for CSOs but also to the CSOs themselves. They are also enshrined in the Charter, which is binding on Member States when they are acting within the scope of EU law (as provided in Article 51 (1)).[49] This may be the case when national laws or practices are implementing EU law, compromise the full implementation of EU law[50] or encroach on fundamental freedoms in the EU.[51] In such cases, the compatibility of national laws and practices with fundamental rights as enshrined in the Charter needs to be checked.

This chapter outlines regulatory hurdles that CSOs have encountered across the EU. Human rights CSOs and their members benefit from many human rights as enshrined for instance in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, the European Convention on Human Rights, and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. This includes the rights to freedom of association (Article 12 EU Charter, Article 11 ECHR, 22 ICCPR), freedom of peaceful assembly (Article 12 EU Charter, Article 21 ICCPR, Article 11 ECHR,), to an effective remedy (Article 47 EU Charter, Article 13 ECHR, Article 2 (3) (a) ICCPR), to a fair trial (Article 47 EU Charter, Article 6 ECHR and Article 14 ICCPR), to property (Article 17 EU Charter, Article 1, First Protocol ECHR) to respect for private life and correspondence (Article 7 EU Charter, Article 8 ECHR, Article 17 ICCPR), and to be protected from discrimination (Article 21 EU Charter, Article 14 ECHR & Article 1, 12th Protocol ECHR, Article 26 ICCPR).

In 2022, the legal situation remained, overall, relatively unchanged from 2021, as both FRA’s consultation findings and Franet research indicate. However, a decrease in challenges related to emergency laws compared with the 2020 and 2021 consultations is visible.[52] This corresponds to the gradual lifting of emergency regulations adopted in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The same applies to challenges linked to travel restrictions and visa bans, which posed less of a challenge in 2022.

However, the overall regulatory environment deteriorated. Two areas were especially problematic: access to information and legislation on civil dialogue. Lack of ability to fully exercise the freedom of expression is the third most common legal challenge encountered by CSOs, according to the results of FRA’s consultation. Moreover, pressure on the right to freedom of peaceful assembly and freedom of association continues to be reported in a number of countries.[53]

Figure 4 shows the challenges that respondents to FRA’s 2022 civic space consultation reported facing in the legal environment.

Figure 4 – Challenges that CSOs encountered in the legal environment in the EU in 2022 (%)

Type your alternative text here.

Notes: Question: “In the past 12 months, has your organisation encountered difficulties in conducting its work due to legal challenges in any of the following areas? You can tick all boxes that are relevant.” N = 381.

Source: FRA’s consultation on civic space, 2022

Overly strict legal requirements for the formation and registration of associations were seen to affect freedom of association. Organisations also faced challenges when establishing their activities and conducting their work.[54] These include measures regarding data protection, transparency, anti-money laundering and tax.[55]

In Bulgaria and the Netherlands, CSOs criticised draft laws that imposed administrative obligations on CSOs funded from abroad as overly restrictive.[56]Compliance requirements and other obstacles continued to be a challenge for NGOs in various Member States.

In Cyprus, CSOs alleged that national laws[57] disproportionately implementing the EU Anti-Money Laundering Directive[58]led to the suspension and closure of accounts and the blocking of funds.[59] In Hungary, CSOs reported that they were being asked to submit large amounts of data as part of an audit planned for in a new law[60] on the transparency of CSOs.[61]

In Romania, CSOs criticised a new law restricting the right of CSOs to challenge building permits and comment on urban planning documents by shortening various deadlines for receiving input.[62] CSOs also expressed their concern that a new law on cybersecurity, requiring security incidents to be reported within 48 hours and the storage of large amounts of data for a long time, and imposing high fines, could also apply to watchdog NGOs and journalists due to its broad scope.[63]

In France, CSOs protested against the requirement to sign ‘republican commitment contracts’ to obtain state approval, receive a public subsidy or host a young person performing civic service.[64] They argued that this violates their right to freedom of association due to a lack of clarity in the contracts, their overly broad scope and the lack of clear remedies for breaches.[65]

In some Member States, measures were taken to facilitate CSOs’ enjoyment of their right to freedom of association. In Finland, the legislature passed an amendment to the Associations Act. It allows associations to hold exclusively virtual meetings, including also general meetings of members of an association , of its executive committees. This enables decisions to be made without the physical presence of (prospective) members.[66]

In Latvia, a new accounting law allows volunteers to perform accounting functions in associations and foundations, and smaller organisations to have simplified accounting processes.[67]

Hampered access to information, the criminalisation of expression, the removal of online content, online and offline verbal harassment, censorship and defamation challenge freedom of expression. Access to information was the most common challenge in the legal environment for CSOs in 2022, FRA’s civic space consultation shows (see Figure 4). National provisions grant access to public documents. However, these provisions include broad exceptions, potentially impeding the proper exercise of this right.

In Malta, the Institute of Maltese Journalists criticised the lack of action on the recommendations of the public inquiry into the assassination of the journalist Caruana Galizia and proposed anti-SLAPP legislation.[68] The Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights also expressed concern,[69] and the Prime Minister agreed to freeze the bills based on the recommendations and scheduled a new public consultation for February 2023.[70] NGOs and the Commissioner for Human Rights also noted difficulties in implementing freedom of information legislation.[71]

In Sweden, legislative and constitutional amendments on the criminalisation of foreign espionage, which include bans on disclosing secret information, may hamper investigative journalism.[72]

In Greece, grave concerns were expressed regarding the use of spyware to monitor the activities of journalists and politicians and alleged SLAPPs against journalists trying to cover stories about spyware (for information on SLAPPs, see Section 2.2).[73]

Improvements are also noted. The Freedom of Information Act in Slovakia was amended to comply with the EU Open Data Directive,[74] expanding the range of entities covered to include more public bodies and insurance companies, and specifying some terms in more detail.[75]

The transposition of the Whistleblower Directive progressed with the proposal and/or adoption of laws in a number of Member States. CSOs in Germany agreed on their own policy to deal with whistleblowers in the civil society sector, seeking to lead by example.[76]

In relation to freedom of peaceful assembly, climate activist-related issues became the centre of attention, superseding COVID-19-related incidents. However, there were still a few cases of the latter. The Estonian Supreme Court justified COVID-19 restrictions on freedom of assembly and other fundamental rights[77] on the ground of protecting life and health.[78] In Cyprus, a demonstration against the full ban on all street protests to limit the spread of COVID-19 resulted in riot charges being brought against 11 participants, who also alleged that the police used excessive force.[79]Slovenia revoked and reimbursed fines that the previous government had issued to protestors during the pandemic.[9] Liberties (2023), Liberties Rule of Law Report 2023

Amid growing public concern about global warming, courts continued to deal with various forms of climate protestors using tactics that violated various laws, including, in particular, traffic laws. For example, in May 2022, 110 climate activists were detained in Denmark for occupying bridges in Copenhagen near the parliament and government buildings. They were released after being interrogated.[80] In Germany, courts punished climate activists for setting up roadblocks and blockades at airports using a variety of criminal laws, amid calls for harsher punishment for their actions.[81]

Climate CSOs called for the discussion of climate change rather than the punishment of civil disobedience.[82] Climate activists were fined in Portugal for disobedience because they refused to end their occupation of high schools and higher education facilities.[83] The Director of the Public Security Police noted that the demonstrations were dealt with in a proportionate and peaceful manner, and the interior ministry noted the importance of young people fighting for their causes.[84]

In a trade union case that could also affect climate protests in Belgium, the Court of Cassation ruled that protestors’ criminal liability for participating in a roadblock on a highway was not excluded based on their right to freedom of expression or freedom of peaceful assembly.[85] Previously, the law had stated that only the organisers of illegal roadblocks would be punished, but the court ruled that participating in such roadblocks was also a criminal offence.[86]

More general problems related to excessive restrictions on peaceful assembly persisted in some Member States. In Greece, an action plan was adopted in 2021 that emphasises the proportionate use of police powers. Nevertheless, there are some reports in the media and among CSOs of the police using excessive force, and allegations of arbitrary arrest.[87]

In the Netherlands, a report by the national section of Amnesty International called for changes in both laws on and attitudes towards public protests, criticising local authorities’ excessive bans or curbs on peaceful assemblies, and many rapid arrests by police at demonstrations.[88] In Spain, CSOs criticised excessive restrictions on freedom of peaceful assembly contained in the Citizen’s Security Law.[89] However, they remained in force[90] in spite of the government’s promises to repeal them.[91]

The issue of SLAPPs has gained more prominence since the European Commission proposed a directive and adopted a recommendation on SLAPPs in April 2022.[92] Coined in 1996,[93] the term “generally refers to a civil lawsuit filed by a corporation against non-government individuals or organizations (NGOs) on a substantive issue of some political interest or social significance” aiming to “shut down critical speech by intimidating critics into silence and draining their resources”.[94] There have been many calls for action on SLAPPs in recent years, including from the Council of Europe, the European Parliament and civil society.[95]

The proposed EU directive on SLAPPs states that human rights defenders “play an important role in European democracies, especially in upholding fundamental rights, democratic values, social inclusion, environmental protection and the rule of law”. The proposal points out that they should be able to participate actively in public life and make their voices heard on policy matters and in decision-making processes “without fear of intimidation”.[96]

For reasons related to EU powers, the legislative proposal covers only cross-border civil cases. Purely national cases are dealt with through an accompanying, non-binding recommendation for the Member States.[97] Negotiations at EU level will clarify the exact scope of the legislation, including the definition of abusive court proceedings, the definition of a cross-border case, and the procedures for early dismissal (the proposal allows courts and tribunals to dismiss cases that are manifestly unfounded) and the protection of SLAPPs victims (including through the provision of legal aid).

Evidence indicates the persisting need for action to curb SLAPPs, especially because, as the proposal notes, none of the Member States currently have any such protection in place. A 2022 Coalition Against SLAPPs in Europe report identifies 570 SLAPPs cases filed in over 30 European jurisdictions from 2010 to 2021.[98]

Additional cases included the lawsuits in Poland that local government entities filed against an LGBTIQ+ activist for calling out ‘LGBT-free zones’, which the courts dismissed. In Austria, the municipality of Vienna has threatened to claim back costs from environmental activists who blocked a tunnel during its construction. Construction was ultimately abandoned after protests from various individuals and organisations.[99] In Croatia, a hotel company filed a lawsuit against activists who had spoken out against the construction of a luxury hotel, citing damage to the company’s image.[100] This triggered activists’ plans to raise money internationally to defend other activists against SLAPPs.[101]

In Slovenia, the Ministry of the Interior ordered protesters and activists to cover the costs of policing unsanctioned events.[102] The ministry under the new government repealed this decision, owing to concerns from CSOs and the Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights that it constituted an effort to excessively limit the right of the protesters and activists to freedom of peaceful assembly.[103]

A number of criminal cases were also opened, by either bringing charges or summoning individuals to police stations. Although the cases were not technically SLAPPs, they were allegedly aimed at stifling human rights activity. They included a criminal law (and trademark) case against an environmental activist in Italy, who faced a lawsuit from the regional government for using the term ‘Pestizidtirol’ (Pesticide Tyrol) instead of ‘Südtirol’ (South Tyrol). In another, the police summoned a Bulgarian journalist to reveal her sources about the affairs of a political party.[104]

Cases can also be brought to both civil and criminal courts, for example as happened to a Croatian activist group that had spoken out against the planned construction of a golf resort near Dubrovnik.[105] The combination of criminal and civil cases brought against them resulted in legal costs, the loss of time to conduct their activities and a more negative perception of the group in society.

|

Box 3 – Promising practice – Countering SLAPPs at national level The Irish Department of Justice conducted a review of civil liability for defamation in light of the potential for SLAPPs, informed, amongst others, by a public consultation and symposium also involving CSOs themselves. It recommended an anti-SLAPP mechanism and the removal of the ban on legal aid for defamation cases, and the use of a public interest defence, the removal of juries and the reduction of legal costs and delays in such cases. Further proposals include “measures to encourage prompt correction and apology” and making it easier to “disclose the identity of an anonymous poster of defamatory material“.* The Media Development Center in Bulgaria announced its plan to offer training to legal professionals on SLAPPs in Bulgaria starting in January 2023. EU-funded projects organise training on this topic in 11 Member States.** Sources: * Ireland, Department of Justice (2022), Report on the review of the defamation act 2009, Dublin, Department of Justice. ** Bulgaria, Media Development Center (Център за развитие на медиите) (2023), ‘Strategic lawsuits against public participation – Workshop on SLAPP or lawsuits aimed at limiting public participation in Bulgaria’ (‘Стратегически съдебни дела срещу участието на обществеността – работен семинар за SLAPP или съдебни дела, насочени към ограничаване на общественото участие в България’), press release, 12 January 2023; PATFox (n.d.), ‘Pioneering anti-SLAPP training for freedom of expression’ |

FRA research indicates that CSOs and human rights defenders, and other activists, continued to face threats and attacks in the EU from both private and public players in 2022.[106] Human rights defenders affected include those in exile in EU Member States, who can face acts of transnational repression.

International human rights law guarantees people the rights to life[107], liberty and security[108]; to participate in public affairs[109]; and to be free from any undue interference in their enjoyment of the freedoms of expression[110], assembly[111] and association[112]. In the EU, similar entitlements are reflected in the Charter, and the Victim’s Rights Directive requires Member States to pay particular attention to "victims who have suffered a crime committed with a bias or discriminatory motive which could, in particular, be related to their personal characteristics" - which may be the case for CSO activists.[10] Directive 2012/29/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2012 establishing minimum standards on the rights, support and protection of victims of crime, and replacing Council Framework Decision 2001/220/JHA, Art. 22

Following up on the European Commission’s 2022 annual report on the application of the Charter and in line with Recommendation CM/Rec(2018)11[113] of the Committee of Ministers to Member States, the Council of the European Union recently invited the Member States to:

[p]rotect CSOs and human rights defenders from, inter alia, threats, attacks, persecution of critical voices and smear campaigns targeting organisations, staff and volunteers by active means, such as by taking targeted actions to address these issues, by establishing monitoring mechanisms to prevent such threats, by ensuring the prompt identification, reporting, investigation and follow-up on such incidents, and by putting in place dedicated support services for civil society actors.[114]

CSOs and human rights defenders continue to experience threats and attacks across all EU Member States. Overall, the vast majority of respondents from across all EU Member States indicated in FRA’s consultation that they had faced some form of threat and attack in 2022.

Around half (48 %) of respondents identified a state/public actor as the main perpetrator of attacks against their organisation, whereas nearly half (46 %) suspected or knew that the perpetrators were non-state/private actors. Moreover, the vast majority of responding CSOs believe that the attacks were linked to the activities and issues the organisations worked on (87 %), or their specific funding sources (30 %).[115]

Such threats and attacks include actions both against organisations and their infrastructure and against their staff or volunteers. They include online and offline intimidation and harassment, negative public statements and smear campaigns, verbal threats, and legal and physical attacks.[116] In several Member States, CSOs reported onc a climate of hostility towards them and human rights defenders: nearly half of CSOs responding to FRA’s 2022 civic space consultation report that media outlets or state actors initiated smear campaigns (see Figure 5).[117]The findings are consistent with the findings of international organisations and CSOs who follow the situation of CSOs and human rights defenders. In some Member States, governments, politicians and high-level officials highlight the vital role of human rights defenders and other civil society actors in promoting rights and ensuring accountability.

Figure 5 – CSOs’ experiences of threats and attacks in the EU in 2022 (%)

Notes: Question: “In the last 12 months, has your organisation, or any of your employees/volunteers, experienced any of the following [types of attacks]?” N = 301.

Source: FRA’s civic space consultation 2022

Figure 6 shows developments over time in the percentage of CSOs facing negative media reports/campaigns, online verbal threats and physical attacks.

Figure 6 – Developments in CSOs experiencing threats or attacks in the EU (%)

Notes: Question: “In the past 12 months, has your organisation, or any of your employees/volunteers, experienced any of the following?” The figure includes those responding ‘often’ or ‘sometimes’ to the question about negstive media reports/campaigns, online vrbal threats, and physical attacks.

Source: FRA’s civic space consultations, 2018–2022

The results of FRA’s 2022 consultation are consistent with findings from previous years. Negative media reports and campaigns were, again, the forms of threat and attacks that responding CSOs experienced most (46 %) in 2022 (see Figure 5). Similarly, the consultation shows that online verbal threats and harassment continue to affect almost half of responding organisations. In addition, more than a third of the responding CSOs claim to have been targets of excessive administrative controls or audits.

Reports of suspected surveillance by law enforcement increased greatly, to 21 % of respondents from 7 % in 2021.[118] At the same time, the criminalisation of and legal actions against civil society activities continue, notably SAR at sea and providing humanitarian assistance to those in need while on the move (see Section 3.2). Legal and administrative harassment, in particular through abusive prosecutions and SLAPPs, are also noted (see Section 2.2).

Threats and attacks particularly affect organisations and human rights defenders working with minority groups, those working with migrants and refugees, those working to combat racism, and those working to promote women’s rights, sexual and reproductive health and rights and LGBTIQ+ rights. The lack of a safe environment for CSOs to fulfil their functions can have an impact on the implementation of the related EU strategies.

Among the consequences of such attacks for employees and volunteers are psychological stress and trauma and financial problems. The attacks can also result in the interruption or reduction of organisations’ activities as a result of external pressure, or employees leaving the organisation (Figure 7). In some cases (6 %), an organisation or an individual human rights defender even had to be relocated to another country, and as many as 4% had suffered physical injuries.[119]

Figure 7 – Impact of attacks on civil society in the EU in 2022 (%)

Notes: Question: “What was the impact of these attacks in the last 12 months on your organisation and its employees/volunteers?” N = 217.

Source: FRA’s civic space consultation 2022

Yet only one in five organisations reported these incidents to a competent body or the media. The main reasons respondents give for not reporting incidents is that they did not regard the incident as serious enough (52 %), they felt that nothing would come out of reporting (34 %), they lack trust in the authorities or the police (17 %) or they find it too much trouble to report an incident (17 %).

A specific development concerns attacks against human rights defenders in exile in the EU. Evidence shows that defenders from non-EU countries in exile in EU Member States face transnational repression from the governments of their home countries in the form or threats and attacks.[120] The NGO Freedom House has documented such attacks occurring in 19 EU Member States since 2014. Transnational repression can include acts such as assassination or assassination attempts, detention, unlawful deportation, rendition, assault, unexplained disappearance, credible threat and intimidation.[121]

|

Box 4 – FRA activity – Report: Human rights defenders at risk – EU entry, residence and support FRA researched how human rights defenders can enter and stay in the EU if they are at risk, and what type of support they would need in 2022. The report was debeloped at the request of the European Parliament and was published in July 2023. FRA suggests ways forward, such as raising awareness of who human rights defenders are and why they need protection, introducing or broadening relocation programmes, more flexibly applying existing visa rules, providing better support for defenders in exile in the EU and reviewing current legal tools for assisting human rights defenders. Source: FRA (2023), ‘Protecting human rights defenders at risk: EU entry, stay and support’, 11 July 2023 |

Human rights defenders supporting migrants, refugees and asylum seekers are facing an increasing number of challenges and risks in their work. These range from verbal threats and physical attacks to smear campaigns and increasing pressure from authorities.[122]

The UN Special Rapporteur on human rights defenders, in her report of July 2022, draws attention to the situation of defenders supporting migrants, refugees and asylum seekers and the particular administrative, legal, practical and societal barriers they face, including in the EU.[123]

CSOs report facing smear campaigns that portray activists as “people smugglers” or “foreign agents”, according to evidence that FRA collected.[124] For example, the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights defenders raised concerns about reports of human rights defenders supporting migrants, refugees and asylum seekers in Greece receiving hostile comments, including from key stakeholders in government.[125]

Pressures from authorities include criminal and administrative proceedings brought against defenders.[126] SLAPPs have targeted migrant rights defenders in at least 12 EU Member States. While the overwhelming majority of cases end with the acquittal of the activists, such lawsuits have the potential to keep the activists occupied, hindering their human rights work, and have a chilling effect.[127]

The situation of civil society players involved in SAR at sea illustrates these challenges. CSOs deploy their own SAR vessels and reconnaissance aircraft, seeking to reduce fatalities in light of the significant numbers of people trying to enter the EU irregularly either to seek asylum or to migrate. Between January and July 2023, NGOs brought 3,777 people to Italian ports, according to the Italian Ministry of the Interior. Although this makes only 4.24% of all sea arrivals, NGOs made a significant contribution to reducing fatalities.[128]

|

Box 5 – FRA activity: Six steps to prevent future tragedies at sea The Mediterranean Sea has become the deadliest migration route in the world, with the International Organization for Migration recording more than 28,000 deaths and disappearances between 2014 and August 2023. Following the tragic shipwreck off the Greek coast on the night of 13–14 June 2023, FRA’s July 2023 report identified six key areas of action to tackle the mounting death toll at sea: ● improved SAR at sea ● clear disembarkation rules and improved solidary between EU Member States to cater for the needs of new arrivals ● better protection for shipwreck survivors ● prompt, effective and independent investigations of shipwrecks ● independent border monitoring ● more accessible legal pathways into the EU. In addition, since 2018, FRA has published regular updates on the number of SAR vessels and reconnaissance aircrafts that CSOs deploy in the region of the Mediterranean Sea, and on ongoing investigations and other legal proceedings against them. Sources: FRA (2023), ‘Preventing and responding to deaths at sea: What the European Union can do’, 6 July 2023; FRA (October 2023) ‘June 2023 uUpdate – Search and rRescue (SAR) operations in the Mediterranean and fundamental rights’, |

CSOs engaged in SAR operations have been experiencing increasing pressure.[129] As some people perceive their presence as encouraging irregular arrivals, they encounter hostile attitudes and face legal proceedings and other measures aiming at blocking their activities. “Their work saves lives and protects human dignity, yet it is being repressed, undermined and obstructed by states”, the UN Special Rapporteur on human rights defenders notes.[130]

Since 2017, Germany, Italy, Malta, the Netherlands and Spain have initiated 63 administrative or criminal proceedings relating to civil society bodies’ SAR operations. Most are proceedings against vessels. One third are criminal proceedings against staff or crew.[131]

These measures need to be examined in light of the broader legal framework relating to search and rescue. International maritime law imposes a clear obligation on vessels to assist all people in distress at sea. Both government and private vessels have a duty to assist people and crafts in distress at sea. Multiple instruments of the international law of the sea regulate this duty.[132]

Acts hindering humanitarian SAR activities may violate states’ obligation to protect the right to life. In addition, deaths resulting from such acts may constitute an arbitrary deprivation of life, for which the state is responsible.[133]

Some of the rescue vessels that CSOs deploy are blocked at ports due to legal proceedings, such as vessel seizures, and cannot carry out SAR operations. The Court of Justice of the European Union recently clarified that the port state may inspect SAR ships of humanitarian organisations and may seize such vessels in the event of a clear risk to safety, health or the environment.[134] However, grey areas still remain in law as regards the permissibility of certain restrictive administrative measures that state authorities impose.

Following a discussion in late 2022, the Italian government introduced Decree-Law No. 1/2023 on urgent provisions for the management of migratory flows. The decree-law obliges ships to proceed to a designated port, often far away from the rescue area, immediately after each rescue operation.[135] In addition to criticism voiced by the European Parliament and UN bodies,[136] NGOs raised concerns that the decree-law “contradicts international law”,[137] slows down SAR actions, and increases the number of deaths and disappearances at sea.

While the coordination of SAR activities is, in principle, the responsibility of national authorities, SAR for persons in distress at sea launched and carried out in accordance with Regulation (EU) No 656/2014 and with international law, taking place in situations which may arise during border surveillance operations at seais also a core element of European integrated border management.[138]

The EU has therefore acknowledged the need for a more structured common framework for cooperation in the field of SAR and has developed a series of policy instruments concerning civil society rescue organisations. As part of the package of instruments, presented under the Pact on Migration and Asylum, Recommendation (EU) 2020/1365 addresses EU Member States with a view to reinforcing information sharing, coordination and cooperation between states and other relevant stakeholders in the field of SAR operations carried out by private vessels operated for this specific purpose. Furthermore, the recommendation aims to ensure that the fundamental rights of rescued people are guaranteed in conformity with the Charter and the principle of non-refoulment.[139]

In 2021, the European Commission established a SAR Contact Group, to facilitate dialogue between Member States and other relevant stakeholders on the implementation of the legal framework for and the evolving practice of SAR.[140] To FRA’s knowledge, two years on, there has not yet been a structured interaction between this contact group and the CSOs deploying SAR vessels and reconnaissance aircrafts.

To engage in human rights work, CSOs need financial, human and material resources and access to national and international (public and private) funding; the ability to travel and communicate without undue interference; and the right to benefit from the protection of the state. The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe’s ODIHR and Venice Commission guidelines on freedom of association note that “the ability to seek, secure and use resources is essential to the existence and operation of any association”. Access to and the use of funding provide associations with the means to operate and pursue their missions and are therefore inherent elements of the right to freedom of association.[141]

In addition, the Council of the European Union recently acknowledged “that civil society actors at all levels need appropriate and sufficient human, material and financial resources to carry out their missions effectively and that the freedom to seek, receive and use such resources is an integral part of the right to freedom of association”.[142]

As regards financial resources, typically CSOs rely on funding and income from a variety of sources. These include the public sector, international organisations, individual donors, foundations and philanthropic organisations, corporations, membership fees and income-generating activities.

Finding and accessing resources remains an ongoing concern for CSOs.[143] In FRA’s 2022 civic space consultation, 58 % of responding organisations often or sometimes experienced obstacles to accessing resources/funding.[144]