Help us make the FRA website better for you!

Take part in a one-to-one session and help us improve the FRA website. It will take about 30 minutes of your time.

Fundamental Rights Report 2016 - FRA Opinions

Focus - Asylum and migration into the EU in 2015

Over a million people sought refuge in EU Member States in 2015, confronting the EU with an unprecedented challenge. Although this represents only about 0.2 % of the overall population, the number was far larger than in previous years. Moreover, with about 60 million people in the world forcibly displaced as a result of persecution, conflict, generalised violence or human rights violations, the scale of these movements is likely to continue for some time.

FRA looks at the effectiveness of measures taken or proposed by the EU and its Member States to manage this situation, with particular reference to their fundamental rights compliance.

In this chapter:

- Significant arrivals strain domestic asylum systems

- EU and Member States’ activities touching on fundamental rights

Download:

Focus - Asylum and migration into the European Union in 2015

(pdf, 1,024KB)

FRA opinions

FRA opinions

- To ensure human dignity, the right to life and to the integrity of the person guaranteed by the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, it is FRA’s opinion that the EU and its Member States should address the threats to life at Europe’s doorstep. To put an end to the high death toll at sea, they could consider working towards a global approach, involving all relevant states and actors, and building on the conclusions of the World Humanitarian Summit, held in Istanbul on 23 and 24 May 2016. They could also consider FRA’s proposals, issued in its 2013 report on Europe’s southern sea borders, on how to uphold the right to life in the maritime context, namely to ensure that patrol boats from all participant nations are adequately equipped with water, blankets and other first aid equipment.

In 2015, over one million refugees and migrants – compared with about 200,000 in 2014 – arrived in Europe by sea, mainly in Greece and Italy. Although rescue elements were strengthened in the management of maritime borders, the number of fatalities in the Mediterranean Sea increased further in 2015. According to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), some 3,771 people died when crossing the Mediterranean Sea on unseaworthy and often overcrowded boats provided by smugglers.

Fundamental rights at Europe’s southern sea borders

- To address the risks of irregular migration to the EU, it is FRA’s opinion that EU Member States should consider offering resettlement, humanitarian admission or other safe schemes to facilitate legal entry to the EU for persons in need of international protection. They should have the opportunity to participate in such schemes in places accessible to them. To respect the right to family life enshrined in Article 7 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights but also to prevent the risks of irregular entry for people who want to join their families, there is a need to overcome practical and legal obstacles preventing or significantly delaying family reunification and to refrain from imposing new ones.

The EU continues to offer only limited avenues to enter its territory legally for persons in need of protection. This implies that their journey to Europe will be unauthorised and therefore unnecessarily risky, which applies especially to women, children and vulnerable people who should be protected. There is clear evidence of exploitation and mistreatment of these groups by smugglers.

Legal entry channels to the EU for persons in need of international protection: a toolbox

- To address the identified challenges, it is FRA’s opinion that, as announced in the EU Action Plan against migrant smuggling, the relevant EU legislation should be evaluated and reviewed to address the risk of unintentionally criminalising humanitarian assistance or punishing the provision of appropriate support to migrants in an irregular situation.

While effective action is required to fight people smuggling, there is a danger of putting at risk of criminal prosecution well-meaning individuals who help migrants. Where citizens seek to help refugees to reach a shelter or to move on to their place of destination, for example by buying train tickets or transporting them in their cars, they are to be considered part of the solution rather than part of the problem. Measures resulting in the punishment of refugees themselves may raise issues under the non-penalisation provision in Article 31 of the UN Convention relating to the Status of Refugees.

- To ensure that the right to asylum guaranteed by the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights is fully respected, it is FRA’s opinion that the EU and its Member States should ensure that their border and migration management policies do not violate the principle of non-refoulement and the prohibition of collective expulsion. The absolute nature of the prohibition of refoulement needs to be respected both in legislative or policy measures and in their implementation. FRA considers that more specific guidance on how to mitigate the risk of violations of the principle of non-refoulement would be necessary to address new situations, such as those emerging as a result of the installation of fences or through interception at sea or enhanced cooperation with third countries on border management.

Increased migratory pressure on the EU led to new measures, including the building of fences at land borders, summary rejections, accelerated procedures or profiling by nationality. There is a general understanding in the EU that we should respect the prohibition of refoulement, but law evolving in this field causes legal uncertainties, as pointed out at the 2014 FRA Fundamental Rights Conference in Rome. Any form of group removal or interception activity at sea could effectively add up to collective expulsion, if the removal or interception is not based on an individual assessment and if effective remedies against the decision are unavailable. Both Article 19 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights and Article 4 of Protocol 4 to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) prohibit such proceedings, with the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) upholding that such prohibition also applies on the high seas.

FRA Opinion concerning an EU common list of safe countries of origin

Fundamental Rights Conference 2014 "Fundamental rights and migration to the EU" : Conference conclusions

- To address the identified shortcomings, it is FRA’s opinion that the EU could consider the risks and benefits of replacing in the long term national processing of requests for international protection with processing by an EU entity. This could, in time, produce a system based on shared common standards. As a first step, and with the effective use of available EU funding, shared forms of processing between the EU and its Member States could be explored to promote common procedures and protection standards, anchored in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights.

A comprehensive fundamental rights assessment at the hotspots in Greece and Italy, covering all phases from disembarkation, initial reception, screening, relocation to asylum and return, would contribute in closing protection gaps that particularly affect the most vulnerable.

Evidence shows that national child protection systems are not always integrated in asylum and migration processes and procedures involving children. More needs to be done to bridge resulting protection gaps and encourage all relevant actors to work together to protect refugee children and, in particular, address the phenomenon of unaccompanied children going missing.

On various occasions and across many Member States, refugees have been recorded as being in desperate and deteriorating conditions in 2015. According to Article 18 of the Reception Conditions Directive, asylum seekers must be provided with an adequate standard of living during the time required for the examination of their application for international protection. Although the directive formally applies only from the moment an individual has made an application for international protection, many of its provisions reflect international human rights and refugee law standards that are effectively binding on EU Member States from the moment a refugee is in a state’s jurisdiction.

Article 18 (4) of the directive requires Member States to “take appropriate measures to prevent assault and gender-based violence, including sexual assault and harassment” in the facilities used to host asylum seekers. 2015 witnessed many well documented reports about women who felt under threat in transit zones and camps. In the case of unaccompanied children, the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights requires that children receive the protection and care necessary for their well-being. Nonetheless, many thousands of unaccompanied children went missing from accommodation facilities in EU Member States, others were kept in detention and again others were separated from their families during chaotic transit or border crossings. Shortcomings like these are due to the high numbers of refugees and the current patchwork of inadequate asylum reception systems. It is not always clear which institutions within the EU and Member States share responsibility for this – a shortcoming the European Commission planned to address in early 2016 through a Communication on the state of play of implementation of the priority actions under the European Agenda on migration.

- Statistics suggest that fewer than 40 % of irregular migrants ordered to leave the EU departed effectively in 2014. Some persons who have not obtained a right to stay cannot be removed for practical or other reasons. Obstacles can include lack of cooperation by the country of origin (such as refusal to issue identity and travel documents) or statelessness. The international and European human rights framework requires that these persons are provided with access to basic services, including healthcare. Making healthcare more accessible for irregular migrants is a good investment in the short and medium term in areas such as controlling communicable diseases, as FRA research indicates. Unlawful and arbitrary immigration detention has to be avoided, while the potential of returns remains underused. Respect for fundamental rights does not pose an obstacle; on the contrary, it can be an important building block towards the creation of return policies.

To prevent ill treatment of forcibly removed people, it is FRA’s opinion that EU Member States should consider establishing effective monitoring mechanisms for the return of irregular migrants. Fundamental rights safeguards in return procedures contribute to their effectiveness and make them more humane, by favouring less intrusive alternatives to detention and by supporting more sustainable voluntary returns as opposed to forced returns. By addressing the issue of non-removable persons, fundamental rights can also make return procedures more predictable. For migrants in an irregular situation living in the EU, FRA in its past reports has called on Member States to respect fully the rights migrants are entitled to under international and European human rights law, be it the right to healthcare or other legal entitlements.

Forced return monitoring systems – State of play in 28 EU Member States

- A significant number of migrants and refugees who arrived in the EU are likely to stay, many of them as beneficiaries of international protection. Given the situation in their countries of origin, return is not a likely option in the near future. Their integration and participation in society through peaceful and constructive community relations pose a major challenge to EU societies. Successful integration of newly arrived migrants and refugees potentially supports the inclusive growth and development of the EU’s human capital and promotes the humanitarian values the EU stands for globally.

To facilitate the swift integration of migrants and refugees in host societies, it is FRA’s opinion that the EU Member States should consider reviewing their integration strategies and measures based on the EU’s Common Basic Principles for Immigrant Integration Policy in the EU. They should provide effective and tangible solutions, particularly at local level, to promote equal treatment and living together with respect for fundamental rights.

1. EU Charter of Fundamental Rights and its use by Member States

Since the end of 2009, the EU has its own legally binding bill of rights: the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, which complements national human rights and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Whereas national human rights and the obligations under the ECHR are binding on EU Member States in whatever they do, the Charter is binding on them only when they are acting within the scope of EU law. While the EU stresses the crucial role of national actors in implementing the Charter, it also underlines the need to increase awareness among legal practitioners and policymakers to fully unfold the Charter potential. FRA therefore examines the Charter’s use at national level.

In this chapter:

- National high courts’ use of the Charter

- National legislative processes and parliamentary debates:limited relevance of the Charter

- National policy measures and training: lack of initiatives

Download:

1. EU Charter of Fundamental Rights and its use by Member States chapter

(pdf, 546KB)

FRA opinions

FRA opinions

- To increase the use of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights in EU Member States and foster a more uniform use across them, it is FRA’s opinion that the EU and its Member States could encourage greater information exchange on experiences and approaches between judges and courts within the Member States but also across national borders, making best use of existing funding opportunities such as under the Justice programme. This would contribute to a more consistent application of the Charter.

According to the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) case law, the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights is binding on EU Member States when acting within the scope of EU law. National courts continued in 2015 to refer to the Charter without a reasoned argument about why it applies in the specific circumstances of the case; this tendency confirms FRA findings of previous years. Sometimes, courts invoked the Charter in cases falling outside the scope of EU law. There are nonetheless also rare cases where courts analysed the Charter’s added value in detail.

- It is FRA’s opinion that national courts when adjudicating, as well as governments and/or parliaments when assessing the impact and legality of draft legislation, could consider a more consistent ‘Article 51 (field of application) screening’ to assess at an early stage whether a judicial case or a legislative file raises questions under the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. The development of standardised handbooks on practical steps to check the Charter’s applicability – so far only in very few Member States the case – could provide legal practitioners with a tool to efficiently assess the Charter’s relevance in a case or legislative file.

According to Article 51 (field of application) of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, any national legislation implementing EU law has to conform to the Charter. The Charter’s role remained, however, limited in the legislative processes at national level: it is not an explicit and regular element in the procedures applied for scrutinising the legality or assessing the impact of upcoming legislation, whereas national human rights instruments are systematically included in such procedures.

Article 51 - Field of application

2. The Charter does not extend the field of application of Union law beyond the powers of the Union or establish any new power or task for the Union, or modify powers and tasks as defined in the Treaties.

- To strengthen respect for fundamental rights guaranteed by the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, it is FRA’s opinion that EU Member States should complement their efforts with more proactive policy initiatives. This could include a pronounced emphasis on mainstreaming Charter obligations in EU-relevant legislative files. It could also include dedicated policymaking to promote awareness of the Charter rights among target groups; this should include targeted training modules in the relevant curricula for national judges and other legal practitioners. As was stressed in 2014, it is advisable to embed training on the Charter in the wider fundamental rights framework including the ECHR and the case law of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR).

Under Article 51 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, EU Member States are under the obligation to respect and observe the principles and rights laid down in the Charter, while they are also obliged to actively “promote” the application of these principles and rights. In light of this, one would expect more policies promoting the Charter and its rights at national level. Such policies as well as Charter-related training activities are limited in quantity and scope, as 2015 FRA findings show. Since less than half of the trainings address legal practitioners, there is a need to better acquaint them with the Charter.

2. Equality and non-discrimination

The EU’s commitment to countering discrimination, promoting equal treatment and fostering social inclusion is evidenced in legal developments, policy measures and actions taken by its institutions and Member States in 2015. The proposed Equal Treatment Directive, however, had still not been adopted by the year’s end. As a result, the protection offered by EU legislation remained disparate depending on the area of life and the protected characteristic, perpetuating a hierarchy of grounds of protection against discrimination.

In this chapter:

- Progress on proposed Equal Treatment Directive remains slow in 2015

- Promoting equal treatment by supporting the ageing population and tackling youth unemployment

- Multiple court decisions clarify Employment Equality Directive’s provisions on age discrimination

- EU and Member States take action to counter discrimination

Download:

2. Equality and non-discrimination chapter

(pdf, 352KB)

FRA opinions

FRA opinions

- To guarantee a more equal protection against discrimination across areas of life, it is FRA’s opinion that the EU legislator should consider all possible avenues to ensure that the proposed Equal Treatment Directive is adopted without further delay. Adopting this directive would guarantee that the EU and its Member States offer comprehensive protection against discrimination on the grounds of sex, racial or ethnic origin, religion or belief, disability, age or sexual orientation on an equal basis.

While benefiting from a solid legal basis from which to counter discrimination, the EU effectively still operates a hierarchy of grounds of protection from discrimination. The gender and racial equality directives offer comprehensive protection against discrimination on the grounds of sex and racial or ethnic origin in the EU. Discrimination on the grounds of religion or belief, disability, age or sexual orientation, in contrast, is prohibited only in the areas of employment, occupation and vocational training under the Employment Equality Directive. Negotiations on the proposal for a Council Directive on implementing the principle of equal treatment between persons irrespective of religion or belief, disability, age or sexual orientation – the Equal Treatment Directive – entered their seventh year in 2015. By the year’s end, the ongoing negotiations had not reached the unanimity required in the Council for the directive to be adopted.

- To ensure a more equal protection against discrimination, it is FRA’s opinion that all EU Member States should consider extending protection against discrimination to different areas of social life, such as those covered by the proposed Equal Treatment Directive. In doing so, they would go beyond minimum standards set by existing EU legislation in the field of equality, such as the Gender Equality Directives, the Employment Equality Directive or the Racial Equality Directive.

The year saw a range of developments relevant to protection against discrimination on the grounds of sex, including gender reassignment, religion or belief, disability, sexual orientation and gender identity. These are all protected characteristics under the Gender Equality Directives and the Employment Equality Directive, with the exception of gender identity and gender reassignment. Although gender identity is not explicitly a protected characteristic under EU law, discrimination arising from the gender reassignment of a person is prohibited under Directive 2006/54/EC on the implementation of the principle of equal opportunities and equal treatment of men and women in matters of employment and occupation (recast). Civil unions for same-sex couples in two Member States became largely equivalent to marriage, except as regards adoption, with marriage for same-sex couples legalised in its own right in one Member State. Discrimination on the ground of gender identity was the subject of reforms in other Member States. Some Member States took steps to address the gender pay gap. Preliminary questions relating to discrimination on the ground of religion and belief were referred to the CJEU for the first time. Some Member States introduced quota for the employment of persons with disabilities.

Protection against discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation, gender identity and sex characteristics in the EU – Comparative legal analysis – Update 2015

Professionally speaking: challenges to achieving equality for LGBT people

EU LGBT survey - European Union lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender survey - Results at a glance

- To ensure that the right to non-discrimination guaranteed by the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights is implemented effectively, it is FRA’s opinion that EU institutions should consider referring explicitly to the fundamental right of non-discrimination when proposing structural reforms in the country-specific recommendations by the European Semester, in particular when promoting gender equality and non-discrimination, as well as the rights of the child. FRA is of the opinion that such an approach would strengthen the postulations made and raise awareness about the fundamental rights dimension of fostering social inclusion.

In continuing to implement measures that address the social consequences of an ageing population, EU Member States contributed to making people’s right to equal treatment under EU law effective. The European Commission’s country-specific recommendations to Member States by the European Semester in 2015 reflect the concern of EU institutions for the social consequences of an ageing population. Relevant country-specific recommendations addressed youth unemployment, the participation of older people in the labour market and vulnerability to discrimination on several grounds, which relates to Article 23 on the right of elderly persons to social protection under the European Social Charter (Revised), as well as to a number of provisions of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, including Article 15 on the right to engage in work; Article 21 on non-discrimination; Article 29 on access to placement services; Article 31 on fair and just working conditions; Article 32 on the protection of young people at work; and Article 34 on social security and social assistance.

3. Racism, xenophobia and related intolerance

Expressions of racism and xenophobia, related intolerance, and hate crime all violate fundamental rights. In 2015, xenophobic sentiments came to the fore in several EU Member States, fuelled largely by the arrival of asylum seekers and immigrants in large numbers, as well as the terrorist attacks in Paris and Copenhagen and foiled plots in a number of Member States. Whereas many greeted the arrival of refugees with demonstrations of solidarity, there were also public protests and violent attacks. Overall, EU Member States and institutions maintained their efforts to counter hate crime, racism and ethnic discrimination, and also paid attention to preventing the expression of such phenomena, including through awareness raising activities.

In this chapter:

- Terrorist attacks and migration into the EU spark xenophobic reactions

- Countering hate crime: full implementation of relevant EU acquis remains elusive

- Tackling discrimination by strengthening implementation of the Racial Equality Directive

- More data needed to effectively counter ethnic discrimination

Download:

3. Racism, xenophobia and related intolerance

(pdf, 422KB)

FRA opinions

FRA opinions

- To address phenomena of racism and xenophobia, it is FRA’s opinion that EU Member States should ensure that any case of alleged hate crime or hate speech is effectively investigated, prosecuted and tried in accordance with applicable national provisions and, where relevant, in compliance with the provisions of the Framework Decision on Racism and Xenophobia, European and international human rights obligations, as well as relevant ECtHR case law on hate speech.

Looking at manifestations of racism and xenophobia, 2015 was marked by the aftermath of terrorist attacks attributed to the Islamic State, as well as by the arrival in greater numbers of asylum seekers and migrants from Muslim countries. Available evidence suggests that Member States that have seen the highest numbers of arrivals are the most likely to be faced with spikes in racist and xenophobic incidents, which will call for the attention of law enforcement agencies, criminal justice systems and policymakers. This is particularly relevant for the implementation of Article 1 of the EU Framework Decision on Racism and Xenophobia on measures Member States shall take to make intentional racist and xenophobic conduct punishable. Article 4 (a) of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination also lays down this obligation, providing for the convention’s State parties to declare an offence punishable by law for incitement to racial discrimination, as well as acts of violence against any race or group of persons.

- To develop effective legal and policy responses that are evidence based, it is FRA’s opinion that EU Member States should make efforts to collect data on ethnic discrimination and hate crime in a way that renders them comparable between countries. FRA will continue working with Member States on improving reporting and recording of ethnic discrimination or hate crime incidents. Data collected should include different bias motivations, as well as other characteristics such as incidents’ locations and anonymised information on victims and perpetrators. The effectiveness of such systems could be regularly reviewed and enhanced to improve victims’ opportunities to seek redress. Aggregate statistical data, from the investigation to the sentencing stage of the criminal justice system, could be recorded and made publicly available.

Systematically collected and disaggregated data on incidents of ethnic discrimination, and hate crime and hate speech can contribute to better implementing the Racial Equality Directive and the Framework Decision on Racism and Xenophobia. Such data also allow the development of targeted policy responses to counter ethnic discrimination and hate crime. Case law of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) and national courts from 2015 further demonstrates that such data can serve as evidence to prove ethnic discrimination and racist motivation, and hold perpetrators to account. Under Article 6 of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, EU Member States have accepted the obligation to ensure effective protection of and remedy for victims. Persistent gaps, nevertheless, remain in how EU Member States record incidents of ethnic discrimination and racist crime.

Making hate crime visible in the European Union: acknowledging victims' rights

Ensuring justice for hate crime victims: professional perspectives

- To make efforts to tackle discrimination more effectively, it is FRA’s opinion that EU Member States could, for instance, consider raising awareness and providing training opportunities to public officials and professionals, in particular law enforcement officials and criminal justice personnel, as well as teachers, healthcare staff and housing authority staff, employers and employment agencies. Such activities should ensure that they are well informed about anti-discrimination rights and legislation.

Although the Framework Decision on Racism and Xenophobia and the Racial Equality Directive are in force in all EU Member States, members of minority groups as well as migrants and refugees faced racism and ethnic discrimination in 2015, namely in education, employment and access to services, including housing. Members of ethnic minority groups also faced discriminatory ethnic profiling in 2015, despite this practice running counter to the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination and being unlawful under the European Convention on Human Rights (Article 14), and the general principle of non-discrimination as interpreted in the ECtHR case law. Article 7 of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination also obliges EU Member States to ensure effective education to fight prejudices that lead to racial discrimination.

- To address the persisting low levels of awareness about equality bodies and relevant legislation, it is FRA’s opinion that EU Member States could intensify awareness-raising activities about EU and national legislation tackling racism and ethnic discrimination. Such activities should involve statutory and non-statutory bodies such as equality bodies, national human rights institutions, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), trade unions, employers and other groups of professionals.

Equality bodies in several EU Member States developed information and guidance documents in 2015 to raise awareness of legislation relevant to countering ethnic discrimination. Evidence shows that, despite the legal obligation to disseminate information under Article 10 of the Racial Equality Directive, public awareness remains too low for legislation addressing ethnic discrimination to be invoked often enough.

- To improve access to justice, it is FRA’s opinion that EU Member States should provide for effective, proportionate and dissuasive sanctions in case of breaches of national provisions transposing the Racial Equality Directive and the Framework Decision on Racism and Xenophobia. Member States could also consider broadening the mandate of equality bodies, which are currently not competent to act in a quasi-judicial capacity, by empowering them to issue binding decisions. Furthermore, equality bodies could monitor the enforcement of sanctions issued by courts and specialised tribunals.

Evidence from 2015 shows that remedies are insufficiently available in practice and that sanctions in cases of discrimination and hate crime are often too weak to be effective and dissuasive. They thus fall short of the requirements of both the Racial Equality Directive and the Framework Decision on Racism and Xenophobia, as underpinned by Article 6 of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination. Furthermore, in only a few Member States are equality bodies competent to issue sanctions and recommendations in cases of ethnic discrimination. How far complaint procedures fulfil their role of repairing damage done and acting as a deterrent for perpetrators depends on whether dispute settlement bodies are able to issue effective, proportionate and dissuasive sanctions.

4. Roma integration

Discrimination and anti-Gypsyism continue to affect the lives of many of the EU’s estimated six million Roma. Fundamental rights violations hampering Roma integration made headlines in 2015. Several EU Member States thus strengthened the implementation of their national Roma integration strategies (NRISs) by focusing on local-level actions and developing monitoring mechanisms. Member States also increasingly acknowledged the distinct challenges Roma women face. Roma from central and eastern European countries residing in western EU Member States also received attention in 2015, as practices to improve local-level integration of different Roma groups were discussed regarding the right to freedom of movement and the transnational cooperation on integration measures.

In this chapter:

- Obstacles to strengthening Roma integration remain

- Going local: implementing national Roma integration strategies on the ground

Download:

4. Roma integration

(pdf, 619KB)

FRA opinions

FRA opinions

- To tackle persisting discrimination against Roma and anti-Gypsyism, it is FRA’s opinion that EU Member States should put in place specific measures to fight ethnic discrimination of Roma in line with the Racial Equality Directive provisions and anti-Gypsyism in line with the Framework Decision on Racism and Xenophobia provisions. To address the challenges Roma women and girls face, Member States could include specific measures for Roma women and girls in national Roma integration strategies (NRISs) or policy measures to tackle intersectional discrimination effectively. Member States should explicitly integrate an anti-discrimination approach in their NRISs implementation.

Ethnic origin is considered the most prevalent ground of discrimination according to 2015 data. Non-discrimination is one of the rights in the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, as well as of several general and specific European and international human rights instruments. Notably, Article 2 (1) (e) of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, to which all 28 EU Member States are party, emphasises the commitment to “pursue by all appropriate means and without delay” to “eliminat[e] barriers between races, and to discourage anything which tends to strengthen racial division”. In 2015, European institutions, including the European Parliament, called attention to the problems of intersectional discrimination and encouraged EU Member States to implement further measures to tackle anti-Gypsyism and intersectional discrimination, also addressing the particular situation of Roma women and girls.

- To address the challenges Roma EU citizens living in another Member State face, it is FRA’s opinion that the EU’s Committee of the Regions’ and the European Commission’s continued support would be beneficial for an exchange of promising practices between regions and municipalities in Member States of residence and Member States of origin.

Member States of origin and destination could consider developing specific integration measures for Roma EU citizens moving to and residing in another Member State in their national Roma integration strategies (NRISs) or policy measures. Such measures should include cooperation and coordination between local administrations in the Member States of residence and the Member States of origin.

Living conditions of Roma EU citizens living in another Member State, and progress in their integration, further posed a challenge in 2015. FRA evidence shows that the respective NRISs or broader policy measures do not explicitly target these populations. As a result, few local strategies or action plans cater to the specific needs of these EU citizens.

- To enhance the active participation and engagement of Roma, it is FRA’s opinion that public authorities, particularly at local level, should take measures to improve community cohesion and trust involving local residents, as well as civil society, through systematic engagement efforts. Such measures can contribute in improving the participation of Roma in local level integration processes, especially in identifying their own needs, in formulating responses and in mobilising resources.

Participation is one of the key principles of the Human Rights Approach to Poverty Reduction Strategies, as outlined by the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) and enshrined in the 10 Common Basic Principles on Roma Inclusion. FRA research shows that in 2015 efforts were made to actively engage local residents, Roma and non-Roma, in joint local-level activities together with local and regional authorities. There is, however, no systematic approach towards engaging with Roma across Member States; structures of cooperation vary greatly, particularly in monitoring NRISs and the use of EU funds.

Local Engagement for Roma Inclusion (LERI) - Multi-Annual Roma Programme

- To address the challenges of monitoring the implementation of local action plans or local policy measures, it is FRA’s opinion that EU Member States should implement the recommendations on effective Roma integration measures in the Member States, as adopted at the Employment, Social Policy, Health and Consumer Affairs Council on 9 and 10 December 2013. Any self-assessment through independent monitoring and evaluation, with the active participation of civil society organisations and Roma representatives, should complement the national Roma integration strategies (NRISs) and policy measures in that regard. Local level stakeholders would benefit from practice-oriented trainings on monitoring methods and indicators to capture progress in the targeted communities.

Practices regarding the monitoring of the local action plans or local policy measures vary within EU Member States, as well as across the EU. In some Member States, the responsibility for monitoring the implementation of these local policies is at the central level, whereas in others it is with the local level actors who often face a lack of human capacity and financial resources. The extent to which Roma themselves and civil society organisations participate in monitoring processes also varies, as does the quality of the indicators developed.

5. Information society, privacy and data protection

The terrorist attacks on the offices of Charlie Hebdo magazine, a Thalys train and various locations throughout Paris in November 2015 intensified calls to better equip security authorities. This included proposals to enhance intelligence services’ technological capacities, triggering discussions on safeguarding privacy and personal data while meeting security demands. EU Member States confronted this challenge in debates on legislative reforms, particularly regarding data retention. The EU legislature made important progress on the EU data protection package, but also agreed to adopt the EU Passenger Name Record (PNR) Directive, with clear implications for privacy and personal data protection. Meanwhile, the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) reaffirmed the importance of data protection in the EU in a landmark decision on data transfers to third countries.

In this chapter:

- Mass surveillance remains high on the agenda

- Fostering data protection in Europe

Download:

5. Information society, privacy and data protection

(pdf, 412KB)

FRA opinions

FRA opinions

- To address the identified challenges to privacy and the protection of personal data, it is FRA’s opinion that, when reforming legal frameworks on intelligence, EU Member States should ensure to enshrine fundamental rights safeguards in national legislation. These include: adequate guarantees against abuse, which entails clear and accessible rules; demonstrated strict necessity and proportionality of the means that aim to fulfil the objective; and effective supervision by independent oversight bodies and effective redress mechanisms.

A number of EU Member States are in the process of reforming their legal framework for intelligence, as FRA research shows, which is based on a European Parliament request to undertake a fundamental rights analysis in this field. Security and intelligence services receiving enhanced powers and technological capacities often trigger such reforms. These, in turn, might increase the intrusive powers of the services, in particular as concerns the fundamental rights on privacy and protection of personal data, guaranteed by Articles 7 and 8 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights, Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), Article 17 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and Article 12 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, as well as access to an effective remedy, enshrined in Article 47 of the EU Charter and Article 13 of the ECHR.

The CJEU and the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) require essential legal safeguards when intelligence services process personal data for an objective of public interest, such as the protection of national security. These safeguards include: substantive and procedural guarantees of the necessity and proportionality of a measure; an independent oversight and the guarantee of effective redress mechanisms; and the rules about providing evidence of whether an individual is being subject to surveillance.

- To render the protection of privacy and personal data more efficient, it is FRA’s opinion that EU Member States should ensure to provide independent data protection authorities with adequate financial, technical and human resources, enabling them to fulfil their crucial role in the protection of personal data and raising victims’ awareness of their rights and remedies in place. This is even more important as the new EU regulation on data protection is going to further strengthen data protection authorities.

Since January 2012, EU institutions and Member States have been negotiating the EU data protection package. The political agreement reached in December 2015 will improve the safeguards of the fundamental right to the protection of personal data enshrined in Article 8 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights. The data protection package should enter into force in 2018. Data protection authorities will then play an even more significant role in safeguarding the right of data protection. Potential victims of data protection violations often lack awareness of their rights and of existing remedies, as FRA research shows.

Access to data protection remedies in EU Member States

- Notwithstanding the discussions at EU level concerning the appropriateness of data retention, it is FRA’s opinion that, within their national frameworks on data retention, EU Member States need to uphold the fundamental rights standards provided for by recent CJEU case law. These should include strict proportionality checks and appropriate procedural safeguards so that the essence of the rights to privacy and the protection of personal data are guaranteed.

Whereas developments in 2014 focused on the question of whether or not to retain data, the prevalent voice among EU Member States in 2015 is that data retention is the most efficient measure to ensure protection of national security, public safety and fighting serious crime. Based on recent CJEU case law, discussions have started anew on the importance of data retention for law enforcement authorities.

- It is FRA’s opinion that, while preparing to transpose the future EU Passenger Name Record (PNR) Directive, EU Member States could take the opportunity to enhance data protection safeguards to ensure that the highest fundamental rights standards are in place. In the light of recent CJEU case law, safeguards should be particularly enhanced as regards effective remedies and independent oversight.

The European Parliament Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs Committee rejected the proposal for an EU PNR Directive in April 2013 in response to questions about proportionality and necessity, lack of data protection safeguards and transparency towards passengers. In fighting terrorism and serious crime, the EU legislature nonetheless reached an agreement on adopting an EU PNR Directive in 2015. The compromise text includes enhanced safeguards, as FRA also suggested in its 2011 opinion on the EU PNR data collection system. These include enhanced requirements for foreseeability, accessibility and proportionality, as well as introducing further data protection safeguards. Once it enters into force, the directive will have to be transposed into national law within two years.

FRA opinion on the proposal for a Passenger Name Record (PNR) Directive

6. Rights of the child

The arrival of thousands of children as refugees in 2015 posed many challenges, including child protection. The European Commission’s efforts to provide guidance on integrated child protection systems was a timely development. With 27.8 % of all children at risk of poverty or social exclusion in 2014, reaching the EU 2020 poverty goal remains a daunting task. Children’s use of the internet and social media also featured prominently on the policy agenda, with the associated risks and youth radicalisation being of particular concern. Member States continued to present initiatives against cyber abuse and on education in internet literacy, and the upcoming EU data protection package will promote further safeguards.

In this chapter:

- Child poverty rates remain high

- Child protection remains central issue, including in the digital world

- Supporting children involved in judicial proceedings

Download:

6. Rights of the child

(pdf, 636KB)

FRA opinions

FRA opinions

- To address child poverty, it is FRA’s opinion that the EU and its Member States need to intensify their efforts to fight child poverty and promote child well-being. They could consider implementing such efforts across all policy areas for all children, while specific measures could target children in vulnerable situations, such as children with a minority ethnic background, marginalised Roma, children with disabilities, children living in institutional care, children in single-parent families and children in low work-intensity households.

The EU and its Member States should consider that measures taken under the European Semester contribute to improving the protection and care of children, as is necessary for their well-being, and in line with the European Commission’s recommendation ‘Investing in children: Breaking the cycle of disadvantage’. These measures could particularly increase the effectiveness, quantity, amount and scope of the social support for children and parents, especially those at risk of poverty and social exclusion.

Five years before the deadline set in the EU 2020 strategy to reduce poverty, child poverty continues to stagnate at around the same high level as in 2010. Children continue to be at higher risk of poverty than adults. Article 24 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights requires that “[c]hildren shall have the right to such protection and care as is necessary for their well-being”. The European Semester attracted criticism for not paying enough attention to persisting child poverty. The Commission’s 2015 announcement on the development of a European Pillar of Social Rights, however, gives rise to some expectations as it refers to the possible development of EU legislation on various ‘social rights’, including the right to access provisions on childcare and benefits.

- To address the challenges of the internet, it is FRA’s opinion that the EU could consider developing together with Member States guidance on how to best implement child protection safeguards, such as the parental consent established in the Data Protection Regulation. These safeguards need to be in line with the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights provisions on the right of the child to protection and the right to express views freely (Article 24 (1).

The internet and social media tools are increasingly relevant in children’s lives, as 2015 research shows. This so called digital revolution brings with it a variety of empowering opportunities, such as child participation initiatives, but also risks, such as sexual violence, online hate speech, the proliferation of child sexual abuse images and cyber bullying. The EU data protection regulation, which reached political consensus at the end of 2015, requires that EU Member States and the private sector act to implement the child protection safeguards established in it.

- To complement recent child-related EU legislation, it is FRA’s opinion that the EU could consider developing together with Member States guidance on how to best implement these new obligations, taking also into consideration the Council of Europe Guidelines on child-friendly justice. Such guidance could address specific safeguards for children in vulnerable situations, such as children on the move, children with minority ethnic backgrounds, including Roma and children with disabilities. Member States should ensure that they effectively implement the Victims’ Directive, particularly Articles 23 and 24, by allocating adequate resources to address aspects such as training (Article 25), professional guidance and material needs (e.g. availability of communication technology, Article 23), all in compliance with the right to protection of children under Article 24 of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights.

Infringement procedures continued in 2015 against seven EU Member States regarding Directive (2011/93/EU) on combating sexual abuse and sexual exploitation of children and child pornography. FRA research issued in 2015 shows that, while some of the procedural guarantees for child victims established in Articles 23 and 24 of the Victims’ Directive were already in place in some Member States, they were not widely applied. A new Directive on procedural safeguards for children suspected or accused in criminal proceedings reached political consensus at the end of 2015 and is likely to be adopted in early 2016.

Child-friendly justice – Perspectives and experiences of professionals on children’s participation in civil and criminal judicial proceedings in 10 EU Member States

Handbook on European law relating to the rights of the child

7. Access to justice including rights of crime victims

With developments in some EU Member States causing concern, the United Nations, Council of Europe and the EU continued efforts to reinforce the rule of law, including judicial independence and justice systems’ stability. Several Member States strengthened the rights of accused persons and suspects with a view to transposing relevant EU secondary law. 2015 also marked the deadline for Member States to transpose the Victims’ Rights Directive, but more work is required to achieve effective change for crime victims. In the meantime, Member States introduced important measures to combat violence against women, and the European Commission communicated its plans for the EU’s possible accession to the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (Istanbul Convention).

In this chapter:

- European and international actors continue to push for stronger rule of law and justice

- Progress on EU directives strengthens procedural rights in criminal proceedings

- Member States’ implementation of victims’ rights

- Countering violence against women

Download:

7. Access to justice including rights of crime victims

(pdf, 447KB)

FRA opinions

FRA opinions

- To address the rule of law concerns raised about some EU Member States in 2015 and prevent further rule of law crises more generally, it is FRA’s opinion that all relevant actors at national level, including governments, parliaments and the judiciary, need to step up efforts to uphold and reinforce the rule of law. They should in this context consider acting conscientiously on advice from European and international human rights monitoring mechanisms. Regular exchange with the EU, and among the Member States themselves, based on objective comparative criteria (such as indicators) and contextual assessments, could be an important element to mitigate or prevent any rule of law problems in the future.

The rule of law is part of and a prerequisite for the protection of all fundamental values listed in Article 2 TEU, as well as a requirement for upholding fundamental rights deriving from the EU treaties and obligations under international law. The UN, Council of Europe and EU continued their efforts to reinforce the rule of law, including stressing the importance of judicial independence and stability of justice systems in the EU. Developments in some EU Member States in 2015, nevertheless, raised several rule of law concerns, similar to those seen in past years.

- To ensure that procedural rights like the right to translation or to information become practical and effective across the EU, it is FRA’s opinion that the European Commission and other relevant EU bodies should work closely with Member States to offer guidance on legislative and policy actions in this area, including an exchange of national practices among Member States. In addition to reviewing their legislative framework on the EU directives on the right to translation and interpretation, and on the right to information in criminal proceedings, it is the opinion of the FRA that EU Member States need to step up in the coming years to complement their legislative efforts with concrete policy measures, such as providing guidelines and training courses for criminal justice actors concerning the two directives.

In transposing the EU directives on the right to translation and interpretation, and on the right to information in criminal proceedings, most EU Member States decided to propose legislative amendments, as FRA findings in 2015 show. They did this to further clarify certain mechanisms put in place by the original implementing laws; to address omissions or issues that arose from the practical implementation of these laws; or to redefine their scope of application. Evidence shows, however, that gaps remain when it comes to the adoption of policy measures.

The right to interpretation and translation and the right to information in criminal proceedings in the EU (INFOCRIM)

- To enable and empower victims of crime to claim their rights, it is FRA’s opinion that Member States should, without delay, address remaining gaps in their legal and institutional framework. In line with their obligations under the Victims’ Rights Directive, they should reinforce the capacity and funding of comprehensive victim support services that all crime victims can access free of charge.

In line with the November 2015 transposition deadline for the Victims’ Rights Directive (2012/29/EU), some Member States took important steps to realise the minimum rights and standards of the directive. Evidence from FRA research shows, however, that significant gaps remain, such as the practical application of information provided to victims (Article 4), establishing and providing support services free of charge (Articles 8 and 9) and individual assessment of victims by police (Article 22). Most EU Member States must still adopt relevant measures to transpose the directive into their national law.

Victims of crime in the EU: the extent and nature of support for victims

- To enhance legal and policy responses to combat violence against women, it is FRA’s opinion that the European Union accedes to the Council of Europe Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (Istanbul Convention), as outlined in the Commission’s roadmap. EU Member States should ratify and effectively implement the convention.

Recognition of violence against women as a fundamental rights abuse, which reflects the principle of equality on the ground of sex, through to human dignity and the right to life, gained more ground in 2015 as four EU Member States ratified the Istanbul Convention and the European Commission announced a ‘Roadmap for possible accession of the EU to the convention’. The need for further legal as well as policy measures to prevent violence against women remains nevertheless. The Commission and individual Member States used data from FRA’s EU-wide survey on the prevalence and nature of different forms of violence against women to argue for enhanced legal and policy responses to combat violence against women.

Violence against women: an EU-wide survey. Main results report

8. Developments in the implementation of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

Five years on from the EU’s accession to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), for the first time in 2015 a United Nations (UN) treaty body, the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD Committee), reviewed the EU’s fulfilment of its human rights obligations. In its concluding observations, the CRPD Committee created a blueprint for the additional steps required for the EU to meet its obligations under the convention. At national level, the CRPD is driving wide-ranging change processes as Member States seek to harmonise their legal frameworks with the convention’s standards. These processes are likely to continue as monitoring frameworks set up under Article 33 (2) of the convention further scrutinise legislation for CRPD compatibility.

In this chapter:

- The CRPD and the EU: a year of firsts

- The CRPD and the EU Member States: a driver of change

Download:

8. Developments in the implementation of the CRPD

(pdf, 404KB)

FRA opinions

FRA opinions

- To allow for a full implementation of the CRPD, it is FRA’s opinion that the EU institutions should use the CRPD Committee’s concluding observations as an opportunity to set a positive example by ensuring rapid implementation of the committee’s recommendations. Representing the EU under the convention, the European Commission needs to work closely with other EU institutions, bodies and agencies, as well as Member States, to coordinate effective and systematic follow-up of the concluding observations. Modalities for this cooperation could be set out in an implementation strategy of the CRPD, as recommended by the CRPD Committee, as well as in the updated European Disability Strategy 2010–2020.

As for the first time a UN treaty body, the CRPD Committee, reviewed the EU’s fulfilment of its international human rights obligations, the committee’s concluding observations on the EU’s implementation of the CRPD, published in 2015, are an important milestone for the EU’s commitment to equality and respect for human rights. The wide-ranging recommendations offer guidance for legislative and policy actions across the EU’s sphere of competence.

- To address the fact that a human rights-based approach to disability is not yet fully endorsed, it is FRA’s opinion that the EU and its Member States should consider intensifying efforts to align their legal frameworks with CRPD requirements. As the CRPD Committee recommends, this could include a comprehensive review of their legislation to ensure full harmonisation with the convention’s provisions. Such EU and national level reviews could set clear targets and timeframes for reforms, identifying the actors responsible.

As the 10-year anniversary of the entry into force of the CRPD approaches in 2016, evidence shows that it has served as a powerful driver of legal and policy reforms at European and national levels. Nevertheless, the human rights-based approach to disability demanded by the convention is yet to be fully reflected in either EU or national law- or policymaking.

Implementing the UN CRPD: An overview of legal reforms in EU Member States

FRA Opinion concerning requirements under Article 33 (2) of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities within the EU context

- To retain the level of involvement the CRPD review process has so far witnessed, it is FRA’s opinion that, when taking steps to implement the CRPD Committee’s concluding observations, both the EU and the Member States should consider structured and systematic consultation and involvement of persons with disabilities. This consultation should be fully accessible, allowing all persons with disabilities to participate, irrespective of type of impairment.

The CRPD Committee’s reviews of the EU, Croatia, the Czech Republic and Germany in 2015 show that review processes by monitoring bodies offer a valuable opportunity for input from civil society organisations, including organisations for persons with disabilities. Retaining this level of involvement and consultation throughout the follow up of the concluding observations presents a greater challenge, given the wide-ranging scope of the committee’s recommendations.

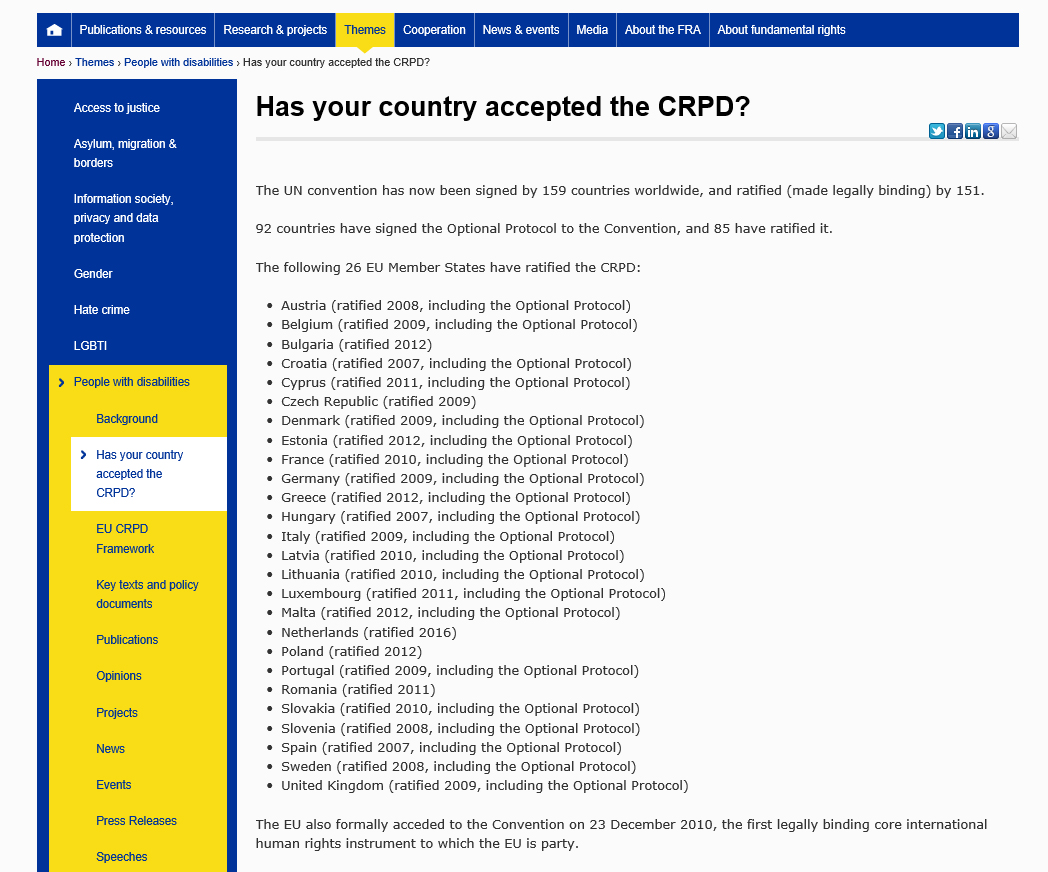

- To achieve full ratification of the CRPD, it is FRA’s opinion that the EU Member States that have not yet done so should consider taking rapid steps to finalise the last reforms standing in the way of CRPD ratification. The EU and the Member States yet to complement their ratification of the CRPD with adoption of the Optional Protocol should consider completing quickly the necessary legal actions to ratify the Optional Protocol.

By the end of 2015, only Finland, Ireland and the Netherlands had not ratified the CRPD, although each took significant steps towards completing the reforms required to pave the way to ratification. A further four Member States, and the EU, are still to ratify the Optional Protocol to the CRPD, allowing individuals to bring complaints to the CRPD Committee, despite each having ratified the main convention by 2012.

Has your country accepted the CRPD?

- To improve monitoring of CRPD obligations, it is FRA’s opinion that the EU and all Member States should consider allocating the monitoring frameworks established under Article 33 (2) sufficient and stable financial and human resources to enable them to carry out their functions. They should also consider guaranteeing the independence of monitoring frameworks by ensuring that their composition and operation takes into account the Paris Principles on the functioning of national human rights institutions, as required under Article 33 (2). Establishing a formal legal basis for monitoring frameworks at EU and national levels, clearly setting out frameworks’ role and scope, would support their independence. Those Member States still to designate Article 33 bodies should do so as soon as possible and equip them with the resources and mandates to effectively implement and monitor their obligations under the CRPD.

At the end of 2015, four of the 25 EU Member States that have ratified the CRPD were yet to establish or designate a body to implement and monitor the convention, as required under Article 33, according to a FRA comparative analysis. Evidence shows that a lack of financial and human resources, as well as the absence of a solid legal basis for the bodies’ designation, impedes the work of those bodies already established, in particular the monitoring frameworks set up under Article 33 (2).

9. EU Member States and international obligations

The standards, procedures and institutions that ensure human and fundamental rights in the EUcover local, national and international organisations including the EU itself, the Council of Europe and the United Nations (UN).

The list below describes key developments during 2015 in relation to a number of core international obligations that the EU and its Member States have taken on. Each heading links to a page where full data can be found.

- Acceptance of selected Council of Europe conventions

In 2015, 10 EU Member States ratified the 15th Protocol to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), dealing with procedural aspects aimed at making the system more efficient; these were Cyprus, Czech Republic, Germany, Finland, Hungary, Lithuania, Netherlands, Poland, Romania and the United Kingdom.

Lithuania and Slovenia ratified the 16th Protocol to the ECHR, allowing for advisory opinions to be requested from the highest national courts.

Cyprus, Germany, Hungary and Poland all ratified the Convention on the Protection of Children against Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse (CSEC). The Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence (Istanbul Convention) saw four more ratifications, from Finland, the Netherlands, Poland, and Slovenia as well as two signatures, from Ireland and Cyprus.

Finland has the highest rate of acceptance of these selected treaties among member states. It has ratified 96.4% of FRA’s list of selected Council of Europe conventions.

- Acceptance of European Social Charter provisions

In 2015, Belgium accepted more provisions of the revised European Social Charter: article 26 (2) on the right to dignity at work; article 27 on the right of workers with family responsibilities to equal opportunities and equal treatment; and article 28 on the right of workers’ representatives to protection in the undertaking and facilities to be accorded to them.

Latvia issued a clarification that it has only partially accepted Article 18 (the right to engage in gainful occupation in the territory of other parties); a clerical mistake had for some time indicated full acceptance ofthis article. It is bound by Article 18 (1) & (4) of the Charter.

- Applications allocated to a judicial formation (ECtHR) per 10,000 inhabitants

This year has seen a sharp increase in applications from Hungary allocated to a judicial formation from the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR). It surpasses Croatia as the State with the highest proportion of applications per 10,000 inhabitants. Statistics released in the ECtHR Annual Report 2015 show that Hungary’s figure stands at 4.30 per 10,000 inhabitants. Croatia meanwhile has seen a decrease in applications from 2.58 in 2014 to 1.92 in 2015. Ireland is again the country with the lowest amount of applications per 10,000 inhabitants at 0.04.

The figures for most EU Member States has remained relatively stable, with the EU average falling again from 0.79 in 2014 to 0.75 in 2015.

- Number of cases pending before ECtHR judicial formations

The number of cases involving EU Member States pending judicial formations at the ECtHR has seen another decrease this year. At year end 2015, 24,417 cases were pending, falling from 26,315in 2014 and 38,303 in 2013.

- Number of ECtHR judgments finding a violation

In 2015, out of the 465 judgments on the 28 EU Member States, the court found rights’ violations in 360 (77%) of cases. This is a proportionate and actual decrease in the number of violations, compared to 2014 where 81% of judgments found at least one violation of the ECHR.

The length of proceedings is still the most commonly judged violation. However, there has been a decrease in the number of violations from 80 cases in 2015 compared with 98 in 2014.

In 2015, there has been an increase in the court finding Article 3 violations in EU Member States because of ‘lack of investigation’. The figure has risen to 28 from 20 violations in 2014, making it the fastest growing category of violation.

Right to an effective remedy is still ranked high among the violations at 65 findings.

- Number of leading pending cases with average execution time of more than five years

Bulgaria, Greece, Italy, Romania, Poland and Croatia all had the highest rates of cases taking longer than five years. Bulgaria has the highest rate at 40 cases, although this a decrease from 2014. However, the overall trend in EU Member States has been an increase in the number of pending cases taking longer than five years.

- Acceptance of selected UN conventions

Three States ratified ILO Convention 189 – Domestic Workers Convention: Finland, Belgium and Portugal. The Convention will come into force in 2016 in Belgium and Portugal.

Czech Republic, Denmark and Finland ratified the Third Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) accepting its individual complaints procedure.

Greece and Italy ratified the Convention on the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances (CED) in the second half of the year. Malta also ratified, but differently from the other two, without accepting the inquiry procedure under Article 33 of the Convention.

- UN conventions with individual complaint mechanisms and number of cases

In 2015, the UN human rights treaty monitoring bodies issued 22 rulings on admissibility and adoption of views. This included: 12 decisions by the Human Rights Committee (HRC) on the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR); five from the Committee Against Torture (CAT); one from the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR); one from the Committee on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW); and one from the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). These rulings concerned eight different Member States. There were nine findings of violations: six under ICCPR (Denmark), one violation under ICESCR (Spain), and two violations under CAT (Finland and Sweden).

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

There have been no further signatures or ratifications of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities or its optional protocol allowing for individual complaints. Thus all EU Member States except Finland, Ireland and the Netherlands have ratified the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). The protocol has 21 parties among EU Member States, with 4 additional signatures (Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Finland and Romania), leaving Ireland, Netherlands and Poland still to take any official action in relation to the CPRD.

- Conformity of national laws and practice with the European Social Charter provisions

In 2015, the European Committee on Social Rights (ECSR) called on Member States to submit information on their law and practices giving effect to provisions in the thematic area “Children, families, migrants”. Conclusions were issued in response to 18 Member States.

The countries who have reported back under the most provisions include the Netherlands (35), Slovenia (34), Sweden (32), Estonia (31), Latvia (32) and Lithuania (31). In total, the Committee examined 434 provisions, between all country reports.

Three Member States conformed to 40% or more of their examined provisions, including Denmark, Hungary and the United Kingdom. 10 Member States conformed to fewer than 25% of their examined provisions: Austria, Cyprus, Estonia, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, Spain, and Sweden.

It should be noted that for some States, conclusions can be deferred, or the ECSR will find a situation of non-conformity where there was insufficient information submitted. Percentage figures are based on which provisions were accepted by the State in question and reported to the Committee.

National presentations

Past presentations

France, 27/06/2016

French presentation of Fundamental Rights Report 2016 to French authorities

France, 19/09/2016

French presentation of Fundamental Rights Report 2016 in Paris at Sciences Po University

Denmark, 05/10/2016

Danish presentation of Fundamental Rights Report 2016 in Copenhagen at conference organised by the Danish Institute for Human Rights

Finland, 17/10/2016

Finnish presentation of Fundamental Rights Report 2016 in Helsinki at conference organised by the Finnish Ministry of Justice and the Human Rights Center

Romania, 16/11/2016

Romanian presentation of FRA’s Fundamental Rights Report 2016 in Bucharest at the International Conference of the Right to Non-discrimination

Slovenia, 22/11/2016

Slovenian presentation of Fundamental Rights Report 2016

Greece, 02/12/2016

Greek presentation of Fundamental Rights Report 2016 in Athens at a conference organised by the Centre for European Constitutional Law